You know when you're talking in front of a crowd and can't find the right words, so you use some filler without thinking through the full implications? We've all been there.

But when you're the CEO and CFO of one of the most important tech companies in the world, and those filler words get recorded at a WSJ event? That's when things get spicy.

Here's what happened: After an in-person interview at WSJ Tech Live, the Wall Street Journal ran a headline saying OpenAI CFO Sarah Frier was supportive of a federal backstop for new AI investments, which—surprise—didn't go over well with global investors who were already having a biiit of a rough week (we'll get to that in a sec).

Here's what she actually said at WSJ Tech Live (lightly edited for readability, but keeping her exact words):

Interviewer: So Sam has alluded to a very interesting new kind of financial instrument for finance and compute. Can you tell us more about what kind of financing he's alluding to and what that looks like where we are?

Sarah Friar: I think on the compute side look first of all the amount of compute required here is massive. So I have been quoted as likening it much more to the dawn of kind of electricity coming into the world. And I think we're at this point where imagine the moment where you put up and back in the day electricity poles, you hung the wire, you attached it to home, and you turned on the light. And we all had lights. Woohoo. I mean, that is an amazing thing. But imagine if we'd stopped there. It feels like where we're at today with AI. We've turned on the lights, but we've not yet thought about how we deploy it to heat a home, to clean a home, to have a TV, to curl your hair, like all the things we today do with electricity. So we're just going getting started. We today the thing I can tell you with absolute certainty we are massively constrained on compute. You're at two two and a half g. We will end this year around 2 gigawatt. And for comparison about two years ago we ended the year at about 200 megawatts. So call it about a 10x in just two years. So imagine if we're on a curve that says we need to 10x again and get to 20 gigawatts in two years. 20 gigawatts. To put in in context, I'm from Northern Ireland. So the the island of Ireland uses about six to seven gigawatts. So we are talking country-sized deployments just to give you a sense of what we're trying to do. So the innovation on the finance side to pay for it is massive. It of course starts with what I said. We've raised equity as a private company. Very kind of typical path, but we've raised a lot. We're building a really healthy business. So, free cash flow, CFO's favorite way to fund anything. That is absolutely climbing quickly. But I think the third area we've gotten into is really working with our ecosystem to do some really interesting financing deals. I'm particularly proud of the AMD warrant structure that we put in place just a few weeks back because it's very strong alignment of incentives. What we've seen is when someone comes out and says, "We're going to work with OpenAI," they im immediately are often seeing kind of impact on their stock price. And so to the extent that that's going to happen, we would like to have some alignment on that. And I think Lisa and team did something incredibly creative with that warrant structure.

Interviewer: Are there more sort of approaches like that that you're thinking of? What what form might that take? Any hints?

Sarah Friar: I mean, I think something along the same lines where where can we create alignment on both sides that when your company does well and our company does well, we get paid together for that outcome. I think that is absolutely an area we continue to go deeper on.

Interviewer: Are there other types of companies that could help, you know, is it banks, is it private equity, is it deeper relationships with the chip companies? Like what's the sort of green space in that at this point?

Sarah Friar: Yeah. So I think from if you look at the world of financing today, the world of financing, let's just talk about a data center build. So a one gigawatt data center build today is about a $50 billion investment. That's for one gig. How that really breaks down is about 15 billion is for the land power shell and about 35 billion is for the chips. And that's real frontier Nvidia chips that we're talking about. The former is well known from a financing perspective. people know how to finance data centers. They typically have 20, 25, even 30-year lives. Those are easy things I would say today to finance. Chips have not been as easy to finance because number one, I think we're all still getting our arms around what is the life of a frontier chip, right? We, OpenAI, at our core are the model company that needs always to be the state-of-the-art. That's what we've done time and time again. GPT-5 is no exception. But even in areas like open source, we're attempting to put the state-of-the-art model always out into the world. And in order to do that, we always want to be on the frontier chip. So the question is, how long does a chip remain on the frontier? Is it three years, four years, five years or even longer? Now in a world where we have no compute, we're compute constrained. We are absolutely using chips that are like A100 equivalents that have been around like maybe six, seven years at this point in time. If that's the case, financing chips gets a lot easier. If the timeline on the chip stays short, that gets harder. And so this is where we're looking for an ecosystem of banks, private equity, maybe even um uh governmental um uh the ways governments can come to bear.

Interviewer: Meaning like a federal subsidy or something?

Sarah Friar: Um meaning like just first of all the the backstop, the guarantee that allows the financing to happen that can really drop the cost of the financing but also increase the loan to value. So the amount of debt that you can take on top of an equity uh portion for.

Interviewer: So some federal backstop for chip investment.

Sarah Friar: Exactly. And I think we're seeing that I think the US government in particular has been incredibly forward leaning has really understood that AI has uh is almost a national strategic asset and that we really need to be thoughtful when we think about competition with for example China. Are we doing all the right things to grow our AI ecosystem as fast as possible?

Interviewer: Are you talking to the White House about how to further formalize that kind of backs stop?

Sarah Friar: We we're always being brought in by the White House to give our point of view as an expert on what's happening in the sector for sure.

Interviewer: Should we, you know, is there something in the works that's tangible?

Sarah Friar: No. No. I I love you, Sarah, but nothing to announce. Nothing that's going on right now.

After this caused a, let's call it "disturbance in the force" on social media, Friar jumped on LinkedIn to clarify she wasn't wink-wink nudge-nudge asking Uncle Sam to guarantee OpenAI's data centers in case they're not able to pay off their $1.4 trillion dollars in financial commitments. Instead, she was pointing out how the U.S. has historically mixed public and private capital to build critical infrastructure like railroads and the internet—so why not AI compute?

But here's why this became "Backstopgate": it wasn't just Sarah's comments.

It was the perfect storm of THREE bearish signals happening at once.

First, Sam Altman told economist Tyler Cowen in an interview making the rounds on social media that for sufficiently large risks, the government becomes the state becomes the “insurer of last resort.”

Tyler Cowen runs an influential economics podcast called Conversations with Tyler and hosts George Mason University's Mercatus Center—basically, he's the guy who interviews top thinkers and policymakers about big ideas. On October 17th, at the Progress Conference in front of a live audience, Tyler asked Sam a pointed question: "The federal government provides insurance for nuclear power plants because people are Nervous Nellies even if the plants are safe. Do you worry the same will happen with AI companies?"

Sam's response was candid:

"At some level, when something gets sufficiently huge, whether or not they are on paper, the federal government is kind of the insurer of last resort, as we've seen in various financial crises and insurance companies screwing things up. I guess, given the magnitude of what I expect AI's economic impact to look like, I do think the government ends up as the insurer of last resort."

But then he clarified what he meant—and here's where nuance matters: "I think I mean that in a different way than you mean that, and I don't expect them to actually be writing the policies in the way that maybe they do for nuclear."

Tyler pushed back: "There's a big difference between the government being the insurer of last resort and the insurer of first resort. Last resort's inevitable, but I'm worried they'll become the insurer of first resort, and that I don't want."

Sam agreed: "I don't want that either. I don't think that's what will happen."

So when the WSJ headline dropped days later about Sarah Friar's comments, it looked like OpenAI was asking to become "too big to fail"—even though both Sam and Sarah were actually talking about something more like infrastructure support (think: government-owned compute that everyone can rent, CHIPS Act-style loan guarantees for fabs) rather than bailouts.

The bailout chatter got so loud that White House AI czar David Sacks wrapped it all up with this gem: "there will be no federal bailout for AI."

Second, and this is the big one, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang told the FT that China would win the AI race. This is not a bullish signal for the US, whose economy is basically reliant on AI dominance in order to continue growing at the current pace. What was his reasoning? Thanks to cheap power and streamlined regulations. We'd also add China’s edge also includes a thriving open‑source ecosystem and a state push to build industrial bases around the stack (what I like to call "kickin' industrial @$$ 'with Chinese characteristics'"). Needless to say, these comments also did not go over well with investors (NVIDIA stock is down something like 8% this week for a variety of geopolitical reasons).

Naturally, faster than you can say "PR crisis," he backtracked, and clarified that China is only “nanoseconds behind America”—a line Huang has used before—and that it's "vital that America" maintains its lead. This includes selling lots of chips to China, as he's argued previously that export curbs can backfire by accelerating homegrown alternatives.

But here's the thing: even the walk-back was basically admitting China's right on America's heels. And given what dropped this week with Kimi K2 (we'll get to that in a sec), Jensen's original comment might've been closer to the truth than his clarification.

Third, Michael Burry—yes, that Michael Burry from The Big Short—disclosed massive put positions on NVIDIA and Palantir. Ah yes, The Big Short guy; always a good sign when he shows up in the news!

This is where the market really started sweating. The guy who called the 2008 housing bubble just bet big against two of the most concentrated AI plays. His thesis? AI valuations have gotten way too concentrated, and when you have that much capital piled into just a few names, you're setting up for a crash.

How big of a crash? The Economist ran an analysis showing that an AI bubble pop could wipe out roughly ~8% of U.S. household wealth—that's about $14.1 trillion. And yet everyone from Reuters to market strategists keep saying "don't panic."

Except the market was panicking. The Fear & Greed index just hit 24 (Extreme Fear)—somehow even more fearful than crypto, which is saying something...

And speaking of crypto: Bitcoin just had its worst week since March, dropping below $100,000 for the first time since June. Over $1 billion in leveraged trading positions got liquidated on Monday alone, with altcoins like Ethereum, Solana, and Cardano plunging 7-10%. The total crypto market cap shed nearly 3% in a single day, erasing roughly $300 billion in value.

What's wild is that crypto and AI stocks are increasingly linked—they attract many of the same investors, so when one trade goes bad, they both get hammered. Bitcoin spot ETFs saw $577M in outflows on November 4th. The Crypto Fear & Greed Index crashed from 58 a month ago all the way down to 20 (deep Fear territory) at its low point—one of the lowest readings since early 2024.

A quick explainer on why selloffs feel worse than they are. Both stocks and crypto lean heavily on leverage—basically borrowing money to buy more. When prices drop, brokers can force-sell your positions (called margin calls), which triggers more selling, which drops prices further. It's why crypto crashes can look like algorithmic waterfalls. For example, over 12 million LINK tokens changed hands in under 30 minutes during Monday's selloff.

For stocks, the VIX Index (the "fear index") is the options‑based gauge that measures how wild traders expect the S&P 500 to swing in the near term is why it's a good signal indicator for bumpy roads ahead. Higher VIX generally = more fear.

So what sparked this panic to begin with? OpenAI is looking at ~$1.4T in spending commitments over 8 years. During a different podcast interview, investor Brad Gerstner asked Sam directly: "How can a company with $13 billion in revenues make $1.4 trillion of spend commitments?" Sam's response was pretty blunt: "If you want to sell your shares, I'll find you a buyer. Enough."

Survey says this answer was not what the market doctor ordered...

This isn't just Sam's problem, though. In general, the hyper-scalers are spending hundreds of billions on datacenter buildouts (something like $400B in total next year). Meta in particular was hit by worried sellers, as many believe its next print should clarify the cadence of capex vs. returns.

Where all that money's actually going? There's all the things Sarah listed ($15B for land, power, and shell, then $35B for chips. Upstream, memory prices are squeezing budgets. TrendForce lifted Q4 DRAM contract prices to +18-23% quarter-over-quarter, with HBM costing roughly 4× DDR5. Street commentary frames AI as capturing an outsized slice of S&P capex (“75% of gains…90% of capex”), explaining why upstream memory and electricity markets are feeling the squeeze.

But as you can see, a huge chunk of AI spending flows directly to NVIDIA's integrated stack—including its silicon, CUDA software, and networking tech. They hold > 90% of the AI training market, were named the "most valuable company" in 2024, and later breached $5T market cap. That concentration is exactly why Burry's short positions and memory price spikes feel so risky—everything's connected.

Before backstopgate, after two days of selling, it had seemed like U.S. stocks had finally stabilized from Sam's selloff, albeit in a lopsided way. Snap jumped on news that it inked a $400M Perplexity deal for in-feed answers launching in 2026. Meanwhile Pinterest fell (−18% day) despite new features, likely hit by tariff concerns affecting ad budgets.

But all of this is why Bloomberg's calling it the "Jenga economy"—uneven, jagged, but rewarding whoever controls the surface where people actually interact with AI. The market's not monolithic, and neither is AI, of course. Some companies are monetizing distribution (Snap, good) while others (Meta) are testing investor patience with massive infrastructure spending.

I think the article that captured the current mood the best was Pomp’s election read: that in Tuesday's election, the people's voice was heard, and they were basically saying the rent is = too high. As a response to the current system, the only logical conclusion is for people to buy assets. But in an aforementioned lopsided jenga economy, the assets worth buying collides with Burry’s concentration short: if everyone crowds into two tickers (NVIDIA and Palantir) as sure things, then it makes those two things easy targets.

And if you want to read as much as we could possibly fit in a single article about whether or not AI investments and valuations today are overhyped (a.k.a a "bubble") or actually undervalued, based on the bull and bear cases for the AI revolution, go ahead and skim through this gigantic deep dive.

Sam Strikes Back...

As you might expect, OpenAI went into full spin doctor mode on Thursday, and in a detailed X post, Sam Altman addressed the backstop issue directly: "We do not have or want government guarantees for OpenAI datacenters." What he is floating? A government-owned "strategic reserve" of compute that anyone could rent, plus loan guarantees for U.S. chip fabs.

Sam also laid out the actual numbers as he sees them. Here are the key takeaways:

- OpenAI expects to end the year above a $20B annualized revenue run rate (that's taking this month's revenue and extrapolating for a full year).

- They're projecting growth to hundreds of billions by 2030, driven by an upcoming enterprise offering, new consumer devices, robotics, and—here's where it gets interesting—"AI that can do scientific discovery."

- On that last point, Sam said they "no longer think it's in the distant future." Translation: they believe AI capable of major scientific breakthroughs is close enough that they need to build the compute infrastructure now.

- As Sam put it: "Given everything we see on the horizon in our research program, this is the time to invest to be really scaling up our technology."

- They're also planning to sell compute capacity directly—becoming an "AI cloud" provider themselves.

- The bet: the world will need way more computing power than what OpenAI is already planning for, so they want to capture that demand.

John Coogan and Jordi Hays of TBPN debated this all on the TBPN live show this week, where John framed the “bull case for backstops” and Jordi compared Sam's proposal to GOCO.

What's GOCO you ask? Government-owned, contractor-operated businesses. Think of it like how the Department of Energy runs national labs. The feds own the supercomputers, researchers rent time on them, but private companies still compete in the market. It's basically infrastructure that everyone can use.

But this only makes sense if the AI chips are actually valuable infrastructure. Railways and transmission lines are worth the upfront cost and the government's time to own and co-operate (or even "backstop") because they are 30+ year investments. Like Sarah said, the jury's still out on how long a chip is considered leading edge (3 years? 5 years? 7 years?). While companies buy and install NVIDIA's current round of chips (for ~$30B, as she said), NVIDIA is already working on the next generation. To their credit, NVIDIA shares their timelines well in advance so companies can plan ahead. Even still, the timelines are pretty aggressive, with the Vera Rubin coming out next year and the generation after that set for 2028.

This is why, in our opinion, energy is the real infrastructure (not chips). While chips turn over every few years, electrons and cooling infrastructure last decades. The IEA warned that AI is pushing data center electricity demand from ~415 TWh and climbing fast (see their full Energy & AI report). And Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella just said that power availability is becoming the binding constraint, not silicon.

This brings us back to China, and why Jensen suggested China could win the race due to power buildout. Turns out, he might've been onto something...

Kimi K2 Thinking, the new open model from China

While American companies debate how to finance their infrastructure, China's open-source ecosystem just leapfrogged several closed models on both capability and cost-efficiency.

China just dropped Kimi K2 Thinking, and it's a genuine landmark moment. This is a 1 trillion-parameter model with 32B active parameters, 256k context window, and native INT4 quantization for efficiency. It can handle 200–300 sequential tool calls and posted scores of 44.9% on HLE and 60.2% on BrowseComp. Docs and API are already live.

But the benchmarks only tell half the story. Here's what people who've actually used it are saying:

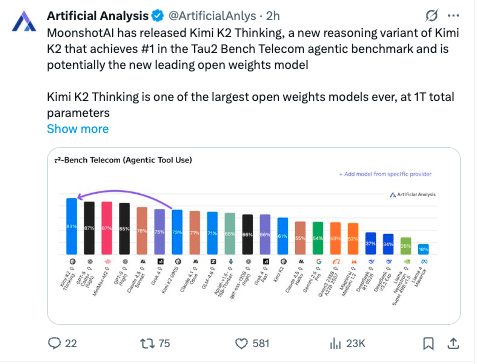

On technical performance: Artificial Analysis called it "potentially the new leading open weights model." It scored 51% on Humanity's Last Exam—higher than GPT-5. It costs $0.60 per million input tokens and $2.50 per million output tokens (roughly 6× cheaper than Claude Sonnet), and runs at 15 tokens per second on two Mac M3 Ultras.

On creative writing: Multiple developers noted Kimi K2 has "genuine literary intelligence"—not just generating words, but demonstrating "taste, structural ambition, metaphorical control, and restraint under extreme constraints." As one user put it: "This model actually accomplishes nearly impossible writing tasks." Another said K2 Thinking "responds more personally and emotionally" than previous versions. K2 was already the best at creative writing, but K2 Thinking is even better...

On agentic capabilities: It's being called "the world's strongest agentic model" and leads specifically on software development and deep research tasks. One developer tested it head-to-head with GPT-5 Pro on highly technical writing with thousands of tokens of context plus agentic search—Kimi came out on top.

On the gap closing: Emad Mostaque (Stability AI founder) said: "The gap between closed & open continues to narrow even as the cost of increasingly economically valuable tokens collapses." Researcher wh noted: "Less than a year ago, open model releases would only compare with other open models because closed models would absolutely cook them. Today, Kimi K2 Thinking stands with the very best."

Menlo Ventures' Deedy Das called this "a turning point in AI"—the first time a Chinese open-source model has genuinely taken the #1 spot on major benchmarks. Specifically, Moonshot AI used quantization-aware training to get native INT4 support, which is why it can run so efficiently while maintaining performance.

Putting all of this in perspective... distribution might be the only moat that matters.

If AI models and chips are heading toward commodity status—and Kimi K2's performance suggests they are—then the real advantage goes to whoever owns the default surfaces where people actually use AI.

Apple is reportedly renting a 1.2T-parameter Gemini model for the new Siri for about $1B annually as a bridge while it builds in‑house, without handing iOS over to Google Search. And Google is moving AI to the default browser surface via anChrome just added a one-tap AI Mode button on Chrome’s New Tab page to keep complex queries (and follow‑ups) in‑flow on mobile. Even Snap signed a deal with Perplexity to pay $400 million over one year (cash + equity) for verifiable answers inside the app starting 2026. These are all distribution plays. Whoever controls the assistant, the browser, or the feed captures the usage.

Open-source models accelerate this shift. They disperse quickly across dozens of neo-clouds and hyperscalers the moment they launch (Artificial Analysis is a great resource to compare providers!), and users can tweak them to their needs and run them virtually at cost. Meanwhile, Sam said only 7% of ChatGPT users had ever tried the thinking mode—the model picker in the platform is itself a barrier to adoption.

What about chips? They're not commodities today—NVIDIA's moat is an integrated system (silicon + CUDA + networking). But commoditization pressures are building as hyperscalers ship their own accelerators (e.g., Microsoft Maia) and Arm CPUs gain share in power‑sensitive DCs (Arm’s data‑center push). You might also want to read our recent story on Google's new Ironwood TPU platform.

Now consider how, when you abstract away the cost to produce the chips at the margins they are produced for, the true cost center of running AI in production is energy. That's why Microsoft's Satya Nadella said power availability—not silicon—is becoming the binding constraint.

By that logic, this cycle's durable asset isn't chips—it's the energy infrastructure that powers them all.

But there's a question buried in all this: If China can deliver comparable performance at a fraction of the cost with open models powered by cheap energy, is the right strategy massive spending on NVIDIA's proprietary chip infrastructure? Or should the U.S. focus on building a competitive energy industrial base that makes affordable compute abundant for everyone?

If, for example, the useful shelf-life of a cutting edge GPU is 3-5 years (as Roblox's CEO suggested on the TBPN pod), then the leading GPUs for training will get turned ovIf AI models and chips are heading toward commodity status—and Kimi K2's performance suggests they are—then the real advantage goes to whoever owns the default surfaces where people actually use AI.

Apple is reportedly renting a 1.2T-parameter Gemini model for the new Siri for about $1B annually as a bridge while it builds in‑house, without handing iOS over to Google Search. And Google is moving AI to the default browser surface via anChrome just added a one-tap AI Mode button on Chrome’s New Tab page to keep complex queries (and follow‑ups) in‑flow on mobile. Even Snap signed a deal with Perplexity to pay $400 million over one year (cash + equity) for verifiable answers inside the app starting 2026. These are all distribution plays. Whoever controls the assistant, the browser, or the feed captures the usage.

Open-source models accelerate this shift. They disperse quickly across dozens of neo-clouds and hyperscalers the moment they launch (Artificial Analysis is a great resource to compare providers!), and users can tweak them to their needs and run them virtually at cost. Meanwhile, Sam said only 7% of ChatGPT users had ever tried the thinking mode—the model picker in the platform is itself a barrier to adoption.

What about chips? They're not commodities today—NVIDIA's moat is an integrated system (silicon + CUDA + networking). But commoditization pressures are building as hyperscalers ship their own accelerators (e.g., Microsoft Maia) and Arm CPUs gain share in power‑sensitive DCs (Arm’s data‑center push). You might also want to read our recent story on Google's new Ironwood TPU platform.

Now consider how, when you abstract away the cost to produce the chips at the margins they are produced for, the true cost center of running AI in production is energy. That's why Microsoft's Satya Nadella said power availability—not silicon—is becoming the binding constraint.

As Ben Thompson argues in the benefits of bubbles, speculative manias often leave useful infrastructure behind; Carlotta Perez’s classic theory shows bubbles financing railroads, canals, and later telecom/fiber buildouts that enable the next S‑curve. By that logic, this cycle's durable asset isn't chips—it's the energy infrastructure that powers them all—the platform all models and chip types run on.

But there's a question buried in all this: If China can deliver comparable performance at a fraction of the cost with open models powered by cheap energy, is the right strategy massive spending on NVIDIA's proprietary chip infrastructure? Or should the U.S. focus on building a competitive energy industrial base that makes affordable compute abundant for everyone?

If, for example, the useful shelf-life of a cutting edge GPU is 3-5 years (as Roblox's CEO suggested on the TBPN pod), then the leading GPUs for training will get turned over at least 1-2 times before Karpathy's 2035 full "AGI" prediction. And what if new chip architectures (like Extropic's thermodynamic computer or new photonic chips) prove to be better than NVIDIA's roadmap?

This actually supports the case for government infrastructure support—not bailouts, but GOCO-style national compute assets that everyone can rent. So any potential "backstop" is a blueprint. Government builds the supportive platform for private companies to compete on top of. Just like it did with rail, roads, and fiber.

Here's the tension in Sam's position: He says (1) OpenAI will pay for infrastructure through massive revenue growth and becoming an infrastructure provider themselves, (2) they should fail if they screw up, but (3) they need government support for fabs and compute reserves because scientific breakthroughs are "no longer in the distant future."

If chips and models are becoming commodities—and if China can deliver comparable performance at a fraction of the cost with open models powered by cheap energy—then the question isn't whether OpenAI can pay for its data centers. It's whether proprietary infrastructure spending on market-valued (a.k.a overpriced) chips is even the right strategy, or if the U.S. should focus on making power so abundant that everyone can compete if they can make a smarter, more efficient chip that runs on smaller hardware.

From that vantage point, I would say that sure, building a shared, government-backed compute resource that accelerates everyone's research is equally valid. But perhaps NVIDIA needs to create a line of chips that are meant for THAT use-case: long-term, sustained use for research purposes.

If NVIDIA can offer the government, say, chips that are guaranteed to be "leading edge" for at least the next ten years (call them "built to last" chips), with a relatively manageable power draw, and perhaps even producible directly in the US at TSMC's new Phoenix Arizona chip fab, then why wouldn't the government subsidize production costs to build out as many supercomputers built on that spec as possible?

Bottom line: The AI race shouldn't be about who has the most powerful chips anymore. IMO, over-indexing on raw compute as the end-all be-all has been an expensive distraction. By believing scaling laws would wash away all sins, we've been trying to shortcut the architectural breakthroughs that experts like Karpathy and Richard Sutton believe WILL exhibit actual intelligence that ACTUALLY scales with compute.

Now, the future is about who can create those efficient breakthroughs that scale better on existing systems, who controls the surfaces where people do and will continue to use AI, and who has the energy to keep it running. On the middle point, US big tech still dominates. On the first and last points, China is almost undoubtedly winning.

So even if not picking winners, per say, the question is "SHOULD the government tip its hand on the scale to change THAT calculation?" You decide for yourself...

For builders, the playbook is clear: Ship on default surfaces where possible. Compress costs with open-source models when you can. Design around the upstream bottleneck (power) that you can't control individually, but governments can address at scale. And maybe complain VERY loudly about the need to create more energy infrastructure ASAP...