Digitizing smell has been historically impossible because while vision only requires mapping 3 sensors (Red, Green, Blue), the human nose has over 300+ distinct receptors. It is a mathematical nightmare that Osmo has finally cracked using a "Read, Map, Write" framework.

We sat down with Alex Wiltschko, the Founder & CEO of Osmo and a former Google Brain researcher, who is doing for the nose what the camera did for the eye. He isn't just building better perfume; he’s building a digitization layer for the chemical world.

Here’s how they are using the "Read, Map, Write" framework for smell right now:

- Scent Teleportation: In a demo, Osmo sensors analyzed a fresh plum, uploaded the molecular data to the cloud, and a robot in another room "printed" the scent. Alex describes the result as indistinguishable from the real thing, capturing the "snap" and tartness of the fruit.

- Generative Scent: Just like Midjourney creates images from text, Osmo Studio allows users to generate custom fragrances from prompts. They even created a scent for the Museum of Pop Culture based solely on a photo of electric guitars (the result smelled like metallic strings and sweat).

- New Matter: The AI isn't just copying; it’s inventing. Osmo has synthesized three brand-new molecules that never existed in nature, including "Glossine," a floral scent that makes perfume last an hour longer.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT: Right now, Osmo is disrupting the $62B fragrance industry by cutting development time from two years to one week. But that’s just the funding mechanism for the real goal: Health.

Alex believes "Air is data." Just as dogs can smell Parkinson's or cancer, Osmo’s "North Star" is to build sensors sensitive enough to detect disease from the molecules evaporating off your skin.

The bottom line is this: We are currently in the "mainframe era" of digital smell—the devices are the size of shoeboxes. But once this tech shrinks to the size of a chip, your phone won't just take pictures of your food; it’ll tell you if it’s spoiled, or even if you are getting sick.

Our Top Takaways From This Episode

Here are the unique insights, predictions, and actionable takeaways from the conversation with Alex Wiltschko, CEO of Osmo, regarding the future of Olfactory Intelligence (OI).

The Mechanics & Science of Digitizing Smell

- The "Read, Map, Write" Framework (1:49)To digitize any sense, you need three distinct tech stacks. For sound, we have microphones (read), MP3s (map/encode), and speakers (write). For smell, we had spectrometers (read) and mixing robots (write), but we lacked the "Map." Osmo is building the AI map to connect the two.

- Why Smell is 100x Harder than Vision (3:32)Vision is based on RGB (3 receptors). Smell relies on over 300 different olfactory receptors. The "map" for smell is infinitely higher-dimensional and cannot be plotted on a 2D graph; it requires AI to find the patterns in the data that humans cannot visualize.

- Story: The "Plum Teleportation" Breakthrough (7:00) A visceral story of the first time they successfully "teleported" a scent. A team member selected a fresh plum in one room; the machine analyzed it, uploaded the data, and a printer in another room synthesized the scent so accurately that Wiltschko could smell the "snap" of the skin and the tannins.

- Neuroscience Insight: Why Smell is Pure Emotion (25:28)Smell is the only sense that bypasses the thalamus (the brain's switchboard) and jacks directly into the Amygdala (emotion) and Hippocampus (memory). Anatomically, when you smell a rose, your brain is physically "touching" the molecules of the rose. This is why scent triggers instant, unavoidable emotional recall unlike any other sense.

Business Applications & Industry Disruption

- The "Tricorder Trap" (Hardware Insight) (15:12) Wiltschko warns that "E-Nose" companies fail because they try to make handheld devices (Star Trek Tricorders) immediately. The winning strategy is to start with massive "mainframe" size lab equipment (mass spectrometers) to build the data model first, and only shrink the hardware after the value is proven.

- Disrupting the 2-Year Cycle (19:46) Developing a commercial fragrance usually takes 1.5 to 2 years. Using their "Osmo Studio" (prompt-to-scent AI), they have reduced the prototype phase to one week, aiming for two days. This democratizes fragrance creation, allowing influencers or small indie brands to launch scents without the "Big 4" fragrance houses.

- Tangent: Smelling a Photograph (21:54) Osmo created a scent for the Museum of Pop Culture based solely on a photograph of a "tornado of guitars." The AI analyzed the image and output a scent described as "metallic strings, sweet, and fresh," proving AI can translate visual input into olfactory output (synesthesia).

Future Forecasts & The "North Star"

- Prediction: The "Framingham Study" for Scent (38:25) We discovered cholesterol causes heart disease because we banked massive amounts of blood in the Framingham Heart Study long before we knew what to look for. Wiltschko predicts we need a similar massive data-banking of "Air" to discover the scent-markers of disease. "Air is data" that is currently being lost.

- Theory: Disease is "Metabolic Exhaust" (41:27) The ultimate goal is disease detection. Internal biological processes (metabolism) produce chemical "exhaust" (volatile organic compounds) that escape through our skin and breath. There is no biological ceiling to what diseases can be smelled; if the metabolism changes, the smell changes.

- Hot Take: AI is "Stacked S-Curves" (47:31) Wiltschko argues that AI isn't a single wave. Text generation (LLMs) is one S-curve that is currently flattening because we've run out of internet data. However, other S-curves (video generation, olfactory intelligence) are just beginning their vertical ascent. Progress is about stacking these different technology curves, not just waiting for one model to become a god.

The Last (Digital) Frontier: How AI is Finally Teaching Computers to Smell

We live in a world where our devices have mastered sight and sound. Your phone can capture a 4K video (sight) and record a crystal-clear voice memo (sound), encoding them into bits that can be sent halfway across the world in milliseconds.

But there has always been a ghost in the machine. A missing sense. If you take a picture of a fresh cup of coffee and send it to a friend, they can see the steam, but they can’t smell the roast.

That is about to change.

The "Read, Map, Write" Framework

Why has it taken so long to digitize smell? According to Alex, the problem isn't capturing the data; it's understanding it. He breaks the challenge down into three distinct stacks:

- Read: We actually already have this. Mass spectrometers (the machines used on CSI to analyze evidence) can look at air and list the chemical ingredients.

- Write: We have this, too. Fluid-handling robots can mix liquids with inkjet precision.

- Map: This was the missing link.

"Vision is easy," Alex explains. "You have Red, Green, and Blue. Three numbers map to every color you’ve ever seen."

Smell is a mathematical monster. Humans have over 300 different types of olfactory receptors. To make matters worse, two molecules can look almost identical structurally but smell completely different, while two molecules that look nothing alike can smell exactly the same.

Osmo used advanced AI to finally build the "Map"—a model that can predict what a molecule will smell like based on its structure.

The "Plum" Moment

The proof is in the pudding—or in this case, the plum.

Alex recounted the day his team achieved "Scent Teleportation." He was presented with vials of liquid representing different fruits. The system "read" the molecular exhaust of a fresh plum, uploaded that data to the cloud, and instructed a printer in another room to reconstruct it.

"It was absolutely engrossing," Alex said. "I was having the visceral sensory experience of biting into a fresh summer plum. The kind with the snap... it was firm, tannic."

They had successfully teleported a physical sensory experience through the internet.

Generative AI for Your Nose

While the sci-fi applications are mind-bending, Osmo is currently applying this tech to the $62 billion fragrance industry.

Traditionally, creating a new perfume is a dark art that takes 1.5 to 2 years. Osmo Studio is trying to turn that into a software problem.

- Text-to-Smell: You can chat with Osmo Studio, describing a vibe, a memory, or a season, and the AI designs the formula.

- Image-to-Smell: In a partnership with the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle, Osmo was given a photo of a tornado of electric guitars. The AI analyzed the visual input and generated a scent that smelled of "metallic strings, sweet, and fresh."

The timeline for creating these scents? It has dropped from years to one week.

The Biology of "Touching" the World

During the interview, Alex dropped a fascinating biological fact: Smell is the only sense where your brain makes direct contact with the outside world.

"When you smell a rose, your brain is literally touching the rose," Alex said.

Visual and auditory signals have to go through the thalamus—the brain's switchboard—before being processed. Smell skips the line. It goes directly to the amygdala (emotion) and the hippocampus (memory). This is why a specific smell can instantly transport you back to your grandmother’s kitchen or a childhood camping trip with a vividness that photos can't match.

The North Star: "Air is Data"

Osmo is selling perfume today, but their ultimate goal is far more critical: Disease Detection.

"What's on the inside gets to the outside," Alex noted. Our bodies are constantly exhausting molecules that serve as indicators of our metabolic health.

- We know dogs can smell cancer, Parkinson's, and seizures.

- We know that "air is data."

The problem is we lack the dataset. We haven't done for smell what the Framingham Heart Study did for blood pressure and cholesterol.

Alex’s vision is to use the commercial success of Osmo’s fragrance business to fund the data collection needed to map scent to health. The goal is to shrink the technology—currently the size of two shoeboxes—down to a chip that fits in your phone.

Imagine a future where your phone notifies you not just of a text message, but that your metabolism is off, or that you’re showing early biomarkers for illness, just by analyzing the air you breathe.

The S-Curve of Smell

We are currently at the bottom of the "S-Curve" for olfactory intelligence. We are in the mainframe era, where the computers are big, expensive, and require experts to run. But as we’ve seen with every other technology, the shrink to personal devices happens faster than we expect.

"Air is data," Alex says. "And we’re just starting to read it."

Complete Episode Transcript

Transcript

(Intro)

Hosts: So imagine if you could smell a photo, not just see it, but actually smell it. Like someone sends you a picture of fresh coffee and your phone releases that exact aroma. Sounds like sci-fi, right? Well, a company called Osmo just figured out how to teach AI about smell.

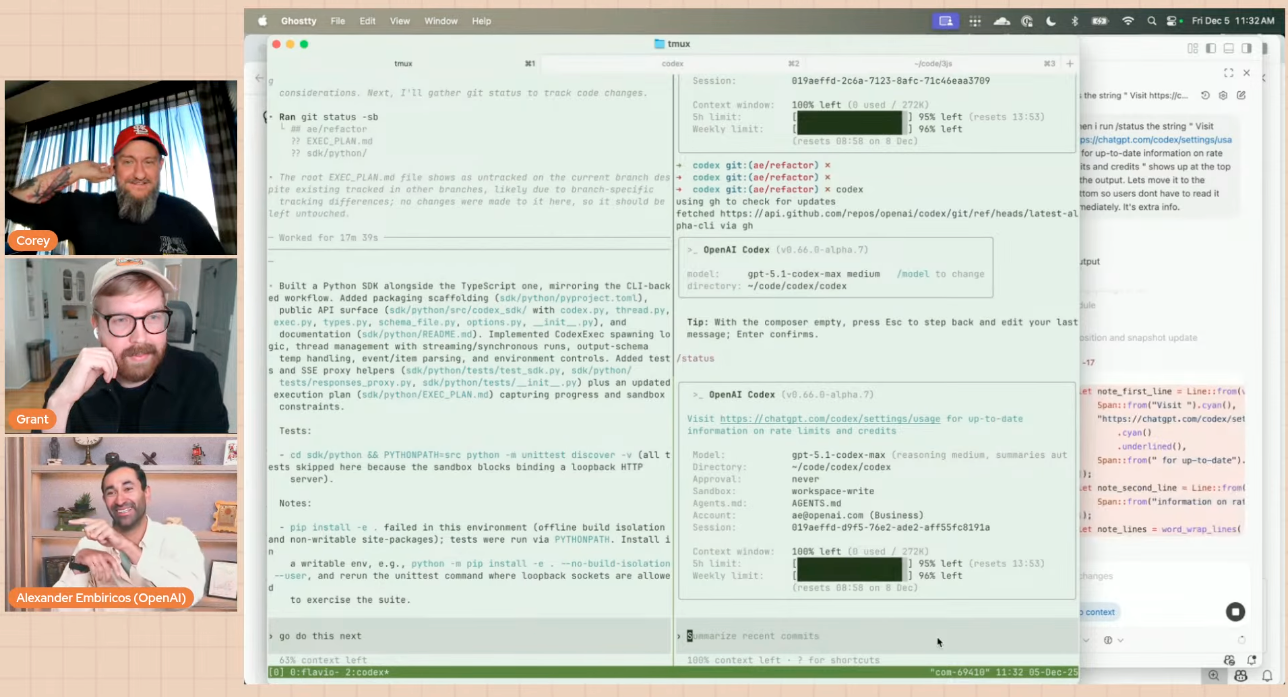

Hosts: Welcome humans to the latest episode of the Neuron Podcast. I'm Corey Nolles, editor of The Neuron, and we're joined as always by the writer of the Neuron Daily AI newsletter, Grant Harvey. Today we are talking about something truly wild, teaching computers to smell. Our guest is Alex Wiltschko, founder and CEO of Osmo, the first company to digitize scent. They've created an AI that can predict what a molecule smells like, teleport scents across rooms, and design brand new fragrance molecules that have never even existed before. And this isn't just about making better perfumes. Alex thinks this could actually help us detect diseases earlier and even fight malaria. That's wild. Alex, welcome to the Neuron. It's a pleasure to have you.

Alex: Corey, Grant, it's awesome to be here. I'm excited to chat.

What does it mean to "digitize smell"?

Hosts: Awesome. Well, I guess first question that everyone's going to be wondering, what does it mean to digitize smell?

Alex: So, I mean, let's let's talk in analogies. What does it mean to digitize sound, which is what we're all experiencing right now? There's three steps. Take the physical world, which is vibrating air waves, and turn that into a digital signal. So that's what a microphone does. That had to get invented at one point, right? Initially, that was literally uh changing those pressure waves into grooves of a needle carving into a piece of physical material. Step number two, encode and uh reason about and then decode that signal. Right? So now we have MP3. Uh it's a way of compressing and understanding audio. We've got audio editors. So first you got to read the physical world. Then you have to map it and then you have to write it back out again. Right? So that's what a speaker does which is it takes those originally just grooves but now digital signals and then it uh moves a surface to recreate those air waves.

The Read/Map/Write framework

Alex (continuing): The important thing about all that is those three steps are wildly different. They're actually three different totally different step uh there. Those are three different technology stacks that each operate under different physical principles, but you have to have them all. And so we're we're looking at digitizing the sense of smell. And we have to do all those three steps. We have to read the chemical world and turn it into digital signals. We have to map it. And then we have to write it back out again. In when we started doing this, I mean, I've been thinking about this problem for about 20 years. And and OSMO's been going for three. And before that, I was I was working on this problem at Google Brain for about six years. What's a little crazy is the ability to read the chemical world already existed. It was really good, actually. There's these things called spectrometers. It's what like CSI uses to figure out, you know, what what are the different trace samples at a crime scene. And then the ability to write the chemical world back out again is also pretty good. There's these fluid handling robots that will move around ingredients and mix them kind of like an inkjet printer can mix inks. The part that was missing was the map. And that's been a super hard problem to crack.

Why smell is 100x more complex than vision

Alex (continuing): And again, let's think about vision. RGB, three numbers that are the map of color. And in fact, we roughly have three different kinds of color receptors in our eye. They roughly correspond to RGB. We have over 300 types of olfactory receptors in our nose. So the sense of smell is going to be just based on that 100 times higher dimensional, 100 times more complex. It whatever map exists for smell is not going to fit on a flat piece of paper. We're not going to look at an RGB diagram and be like ah that's why you know lavender smells close to this other floral but far away from rottex. Not going to happen. The map exists in data though, right? So that's the core insight that we've been operating around is like well now we have algorithms and we have huge data sets and we don't need to wait for our own visual cortex our own visual systems to lead us to the map. We don't draw it on pieces of paper. We we extract it from from data. So that that's that's kind of the core insight and then we reuse a ton of amazing technology and we stitch it all together.

Hosts: So when did you realize that this was even possible?

Alex's origin story: 20 years in the making

Alex: So, um, I got really into this problem. Let me back up. I got really into smell when I was very young. Like me and my dad would play guess the spice when we went out to eat and try to figure out like, hey, is what what's the smell here? What's the aroma here? I got really into perfume and perfume collecting when I was about 12. I was already a big computer nerd and computer programmer, so adding like perfume collecting in like a very small Texas town does not like make you the most popular boy.

Hosts: That's fair.

Alex: Um, but you don't choose your obsessions, they choose you. And then I I watched a TED talk by a guy named Luca Turan uh when I was in I think I was in college. And the TED talk said two things. One is, you know, we really don't actually know why things smell the way that they do. And then number two is he had a solution for it. I I turns out I think that that's mostly wrong the solution, but oh my gosh, is there value in asking the right question? And this idea that like you can tell me RGB and I can I can figure out what color that is. It seems trivial. We can't do that for smell. Like we we can't talk about why something smells the way that it does. It's just random. And then I ended up going completely down that rabbit hole. And I ended up uh and you know I did my undergraduate neuroscience. I got my PhD in olfactory neuroscience and I learned that actually nobody knows the answer. Like you go to the very edge of human knowledge, at least in academic science. And and there's no answer forthcoming for something that seems very basic. It drove me absolutely bananas. And that's basically been my life's work since then is trying to figure this out.

The scent teleportation breakthrough

Hosts: So, in 2024, you achieved scent teleportation. That's right. Uh, it was a fresh cut plum, uh, from what I understand. And what happened that day? What was that that day like? How did the project go? Tell just just kind of walk us through it if you would.

Alex: One of the wildest, most excellent days in my professional life was that first breakthrough. And it was really just a first step. Like, it's not the top of Everest. It's like getting to base camp, but it's still so so powerful and so vivid in my memory. So, the team had been working for a while on the technology and the processes to do this. And one day they said, "Hey, look, I think we're ready." And they uh sat me down in the morning in front of 30 amber vials. And inside of these vials, blind to the entire team, been set up by somebody else, blind to the entire sent teleportation team, uh, inside of it were fruits and vegetables and some flowers. And so they didn't know what I was going to choose, but these were real things from the grocery store. And I think what I picked was uh, a banana and it was a tropical fruit. I think it was um, a papaya. Uh, and this is just by smell and then I verified it later. And then a plum. And we put each three of these through the teleportation process, which is you show that scent to a device that was specially tuned and set up to analyze the molecular content of that smell. The data was uploaded to the cloud and analyzed by the AI systems that we built. Um, and really it's AI for scent. Um, we call that old factory intelligence or OI. And then it was reprinted on uh our smell printer which we had custom programmed to work with the fragrance ingredients that we see in the real world. And the first smell that came off was plum. And it was absolutely engrossing and transporting that I was smelling this a blott dipped into a vial of clear liquid and I was having the visceral sensory experience of biting into a fresh summer plum. Like the kind with the snap when you bite into it, it's still firm. It's a bit tanic. But like my whole kind of consciousness was filled with the experience of having just bought into a snappy of just having bought into my sensory experience.

Hosts: Yeah.

Alex: My sensory experience was was filled with the experience of biting into a fresh summer plum that still had a snap to it. And I was like, "Wow, my gosh, it works." Like no human was involved in actually looking at the data. There was it was all instrumentation and robotics and and software and we actually we transported a plum from one room to the other. It was incredible.

Hosts: It's amazing. So cool. That reminds me of like um hear you know reading stories about Alexander Graanb and like people like in the early days of like figuring out the audio and how you send messages like to each other. Like it reminds me of that sort of level. Um, I have to ask as well, just this is a slight side tangent because the way that you're describing this is is really really visceral. It really draws me in. Have you ever seen the show Drops of God on Apple TV?

Alex: So, I read the manga because I'm a big nerd.

Hosts: Okay. Um, and uh I fellow manga nerd. Yeah. Um, and I watched the first couple episodes, but that like the intensity with which they portray the sensory labeling is like so extra and I love it. Yeah. For people who don't know, it's a great show about uh essentially a a famous wine uh what do you call it? A Somalia is the person who can smell and describe and knows about the world of wine.

Alex: Yep. Yeah.

Hosts: who who gives away like basically dies and and wills his fortune to uh his protege and his daughter and they have to compete in a test to see who is worthy of his $150 million wine collection and they just capture smell like so excellent on that. They almost have like a an exper like a spiritual experience when they smell it. And she in the show um did what you were talking about with the spice testing where you know as a young girl she was supposed to taste stuff and try and smell it.

Alex: I've heard really guess it was it was tasting as opposed to smelling.

Hosts: Yeah.

Alex: And in 90% of flavor is smell, right? So there's just there's a few things on your tongue and they're they're important, but uh the the experience of wine, uh much of that is going to be through your nose. So like if you have a cold or if you plug your nose, like it's just going to be sour or bitter or tanic. You're not going to get the reason things don't taste right when you're sick.

Hosts: Exactly.

Alex: Exactly. Because you know what what happens is you drink something or you eat something, you chew it, it creates a chimney of basically steam and aerosol that actually goes back up your nose. It's called retronasal action. So you're smelling as you're as you're eating.

Hosts: Wow. Wow. I didn't know that. So, so like you mentioned the read map write framework, right? Where you're reading it, you're then mapping it and then you're writing it back. Um could you just explain like in terms of like your system specifically like what is actually happening cuz you said there like three different like like systems that work together I guess.

Alex: Yeah. So re reading uh is about using existing chemical sensors to turn molecules into digital signals and that's a really old tradition more than 12 years old. Basically taking a piece of chemistry and turning it into electrons or photons and um there's a bunch of different ways of doing it. Um many of them fall under the label of spectrometry which just means measuring you know measuring uh uh physical things and um the kind of spectrometry that astronomers do looking at the stars you know the fundamental principles are kind of the same of what we do when we really you know dial in on ascent. We use different physical principles, but the idea is we're trying to figure out what's the matter with the, you know, in in in the cone of of of perception that we're that we're pointed at. Um, and so we use spectrometers in order to turn chemistry into digital signals. Um, normally before OSMO, very very well-trained, specialized people would look at that data. And, you know, that's still mostly the way that that data is interpreted is by people. Um, and what we've developed is a suite of AI tools to either augment in some cases uh or automate the analysis of the data that comes off of those devices. And that's that creates a fire hose of data for us. So we know what different physical things smell like. We know what different market products smell like. And that's our our core business is we actually design fragrances for brands. That's the the the way in which we're building the business to continue funding the curiosity to move to the next step of Shazam for smell and then to move to the next step of sniffing cancer.

Hosts: Shazam for smell.

Alex: We smell we we we sell perfumes to get the Shazam for smell and then we build both of those businesses to ultimately detect disease which is that's the holy grail. That's our north star.

Hosts: That's amazing.

How close are we to sending scents like photos?

Hosts: How how close are we to then like sending sense or or detecting sense on like our phones like we send photos?

Alex: Yeah, I I mean I can see a path to detecting scent already today. We do that for some customers. So we there's an article about this online, but we've uh sniffed fake Air Jordans at StockX. So fake shoes smell different than real shoes, and that has to do with how they're constructed. So, we have a we have a we already have a team and we already have a technology that can smell as well as our nose can. That's not our main our main business today. So, we want to continue to develop the technology to take it from the size that it is, which is not small, but it's not big. You can hold it and and move it around. We want to make that something that is moving towards being pocketable and and more affordable. It's not quite yet affordable, but it already solves real world problems today, but we're going to continue to develop it. um getting it to something the size of your cell phone may require scientific breakthroughs that we can't even describe today. So, I want to be real. Like, that's why we're taking the strategy that we are. Like, I've looked at all the ENOS companies. Um, I've looked at all the old faction companies and that I that I've been able to find at least, and every single one of them that kind of aimed for that that Star Trek triquarter vision, but didn't chart a path through kind of a reasonable business. All of them that went right for the mountaintop, they're they're all dead. And it's not because they weren't working hard enough. It's because it's so freaking hard, right? Like to solve that problem may require hundreds of millions or or likely billions of dollars to build a device that can do what we really want it to do, which ultimately is what a dog's nose can do, which is detect disease and detect, you know, produce at borders or drugs at borders. Like to to keep people safe and to keep people healthy. We want a device that you can hold in your hand, in your pocket, that smells as well as a dog's nose does. And like I actually don't think anybody knows how to build that in short order. Um, the world can change in an instant, so who knows? But to really do that, well, what the tack that we've taken is like you have to look at that with complete humility and understand that like, man, before that thing gets small, it's going to be big as with all technology. And before things are even in your home, they're going to live in a like a warehouse or a special room, which is like, think about computers. Like mainframe computers in the 1960s filled up a whole room and had specialized staff on it. Huge. Then they got smaller by the time Bill Gates came around. Like you still there personal computers, right? He had to break into a a company or a university to use a computer. Um and then they became personal, right? So, like we're in the realm now where the ability to create smell and to read smell exists, but it has to be enclosed in a laboratory and in a factory, which is why we have both of those things cuz we can't fit a mass spectrometer into our phone yet. We cannot fit a mass spectrometer into our phone yet. But we're we're going to get there. Like, people are ingenious. like you know it might either come from one of you know folks at our company from an osmanot or it might come from outside of our company in an academic institution or another like somebody's going to figure this out and you know we'll be there to help make sure it happens faster. Um but like man we're going to get there 100% we will.

Launching Osmo into the fragrance industry

Hosts: So you launched Osmo into the fragrance industry. Uh what's the response been like?

Alex: Uh it's been overwhelming and so we have uh more work than we know what to do with at this point. meaning we're using OI to design beautiful fragrances and we're we're we're working our absolute best to keep up with the demand. Uh in fact, we're opening up a new factory in order to keep up with the demand. We learned a few things. Um, we we've worked with a number of different customer sets and what we've learned is there's a lot of people out there who love smell and a lot of people out there who want to create beautiful scents and add it to their their company, their brand and not just like perfume brands. Like you'd be surprised like there's a lot of individuals out there that have a following online and want to launch their own fragrance, right?

Hosts: And they don't want to promote somebody else's. They want to design their own. They want to do it themselves.

Alex: Exactly. That makes perfect sense. And so, you know, it used to be really hard to even make your own visuals or edit your own video. Everybody can do it now. And so, what we're finding is that lots of people want to make their own scent and we can actually help them do that. So, what we designed was uh this software experience called Osmo Studio and it basically lets you design the scent.

Osmo Studio: Design your own fragrance with AI

Alex (continuing): So, you talk to it, you type into it just like a prompt and chat GPT. You can select certain things like, hey, I really want this fragrance note or, you know, I want this to be unisex or I want to wear this at night. It turns out there's some, you know, subtlety to how you construct the fragrance to make all those things make sense. And then you hit build my scent and you hit buy and we send you a sample and actually three samples in a box of completely OI generated scent that matches the emotional experience that you're trying to create. And we've gotten amazing feedback from it. like we we've we we kept it in a very small closed beta and we're going to be opening it up more and more over time, but you know, people are smelling it and they're saying, "Oh my gosh, this is exactly what I wanted." Some people are saying uh and more and more over time are saying, "I actually want to turn this into a brand. Like, let's launch it." And that's kind of where our demand is coming from. Uh and so this is really really new and really really special.

One week vs. two years: Disrupting fragrance timelines

Alex (continuing): So, the normal way you design a scent at the industry could take you a year and a half or two years to get your scent finalized and launched. And what we're finding even with the state that we're in today is that we can get people their first scent in one week. And we hope to get that to two days uh and not too long. And then people can launch their whole brand in three or four months. And we have a wait list now. And so that's that's um uh that's what we're able to do kind of with the current customer set. But we we hope to take that down much much less. So it's kind of turning the industry on its head where like it's there's not there's not a scent designer or perfumer hidden away somewhere. It's you like you you're creating the scent which is which is super beautiful and fun.

Hosts: You don't have to buy some celebrities set anymore.

Alex: Yeah. You could be the celebrity, you know, like you could design a scent and launch it online and like totally capture the zeitgeist and then it could be the Cory and Grant, you know, neuron scent that really really captures the moment that's super beautiful and and addictive. And I think that's what we need.

Hosts: Grant Yeah, we need to launch a scent. Corey smells like a orange cat. An orange cat. That's that's a pretty good name for a fragrance to start like canvas your audience. Would you buy, you know, Oda orange cat and we can make that a reality? Actually, we should we should totally do this, Cory. That's that's awesome. Um, we will take you up. Science, you know, that's that's possible.

Creating scent from images and music

Hosts: I have a I have a funny question. So, you mentioned like you can do this via chat now. So, you know, chats are going multimodal. Could you upload like a song or an image and say like give me the vibe of this? Like how long would you do that?

Alex: We we actually launched um we launched a product at the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle and if you go there, you go to the gift store and actually soon we hope bigger retailers, you can buy the scent of that museum experience. The only thing they gave us to create that scent was a picture of a 30 foot tall sculpture of like a swirling tornado of electric guitars.

Case study: The Museum of Pop Culture scent

Hosts: Oh wow. So the the input was this image of like a ton of like you know instruments, rock guitars and the thing that came out of the scent that came out of that process smells like the metallic strings of the guitar.

Alex: It's sweet and it's fresh and it's like you know lively and they put in we I mean they ultimately launched the product but we put it in a bottle for them. We put it in a package for them and it's in the gift store, right?

Hosts: That's so cool. Wow. Or what's another place that has like a really distinct smell that people... Oh, I've seen this. So, there's a candle online that it recreates the smell of going on the ET ride at Universal Studios.

Alex: Okay. Have you seen this before?

Hosts: No, this is new to me. Who sells it? Like there uh I don't know who sells it, but I've I've seen this uh perhaps on Etsy or somewhere. And uh people really like this because appar allegedly this place had a very distinct smell. I think because of the smoke uh machines that they would use and...

Alex: Okay, that's so funny.

Hosts: Yeah. And so that's like you got to find these places where they have a really distinct smell that people like and and try and recreate that because that's an awesome...

Alex: Yeah. And smells so powerful. It's super powerful, right? So that's I mean that's what we want to honor and tap into is like people want to create, people want to explore and I think if we create the ability for people to express themselves, you know, even if it's some crazy new modality like scent, I think the empowerment that comes from that is is really beautiful.

Why smell memory is so powerful

Hosts: Actually, I'd love to get your take on this because I have heard this before, but I don't know the science behind it, so I'm interested. Um I have heard that your uh however the the sensors in your nose your natural sensors work uh it because they die very quickly they have to encode uh information really fast. I don't know if that's actually how it works. You can tell me but um that that means that like when you have uh you can have a very strong smell memory uh to to remember things and it's really powerful like to the point where it can take you back to a moment in time if you smell like a certain type of smell. And so that makes me wonder if it's possible to, you know, have a picture and then that could maybe even like like from your past take take you back to that moment. Camping trip with your grandparents as a kid or I mean Yeah. Could you explain just how that works?

Alex: Yeah. So there's there's three pieces to that. Like one is what happens to the alactory receptors like h how do they work? Um and then why is smell so emotional and can you can you tap into that and basically transport somebody back to a moment. So the first is olfactory receptors do we call it turnover meaning the olfactory sensory neurons that are like the the cells at the top inside at the top of your nose it actually do the sensing they don't live forever um they're because they're in direct it's your brain directly touching the world right.

Your brain is literally touching the rose

Alex (continuing): So like your brain leaves your skull that is what smell is so when you smell a rose your your brain is literally touching the rose so th those cells get subject to a lot of environmental, you know, change and so they they do die and the brain replenishes them. And so this is why if you lose your sense of smell, you're waiting like two weeks for it to start to come back. That's the transit time for neurons to come, you know, and regenerate the ones that are lost. It's happening continuously though. Um then number two is like why is it so emotional and why is it also so tied to memory? And that's because it's directly jacked into your centers of emotion and your centers of memory. So every other sense before they can create memories or can create emotions have to go through a bunch of steps. And one of the way stations in the brain is called the phalamus. Smell is so old evolutionarily it skips that. So it goes directly to the signal once it's kind of collected outside of the nose inside of the skull in a place called the alactory bulb. It goes right to the amygdala which is the seat of emotion and it also forks and goes at the same time right to the hippocampus which is the seat of memory formation. So smell is privileged anatomically in terms of how it's wired in your brain. And that is why it can create these immediate emotions, these immediate memories. And why you smell something once you associate it with a memory, 20 years later, it's instant recall, unavoidable. You can't even fight it. Um, and that's because of how it's wired in your brain. And then can we tap into that? And the answer, I think, is going to be yeah. Then and I I think about how photographs...

The future of scent memory (like photos changed memory)

Alex (continuing): ...changed our relationship with memory in 1820 1825 just to be you know have two a nice brown 200 years ago. If you saw a beautiful sunset with your with your son or your daughter the impression of that sunset and what your child looked like at that age. Everybody just didn't think anything of it being permanent. It was ephemeral. So when your child got older, their face as a child is gone, unless you could afford to pay for a painter, which is super rare. In that very moment, that sunset is also gone forever. And then fast forward until the late 1800s, all of a sudden there's this thing called the camera. And you can actually hold on to light like just what the world you can just hold on to that that's crazy. And then the photograph also came around and then ultimately you know recorders that people could hold you know many decades later all of a sudden the sound of your grandma or of your child like you can just hold on to that forever. That's crazy. And I I think that what what we're building at Osmo, although we're very focused on creating fragrances and building a business so we can reinvest in curiosity, but where where we're going is being able to engage with a kind of memory that we think we just assume will be gone forever. We just assume it's gone forever and it doesn't have to be, right? So, you know, our our our kind of super secret plan is, you know, build fragrances for the world's brands because what's crazy is the molecules that are in fruits and flowers and vegetables that go into beautiful scents that are sold on shelves. Those are the same molecules that you find in the smell of your loved ones and that you find in the smell of human disease. Now, the ratios are totally different, right? So the signal, the fingerprint that you get from each of those is wildly different. But nature reuses these molecules. And so if you get really good at building market ready products, you're actually secretly teaching yourself how to understand and decipher and detect the smell of disease. And also the the infrastructure you need to go and build those things actually means you have to build a lot of sense and analyze a lot of sense which looks like a fragrance factory, right? So We're very fortunate that we've been able to find this path where like the business and the strategy are like right on top of each other. And in fact, like when people buy a fragrance from us, they may or may not know it, but they're funding the ability to detect disease early with smell. They're directly funding the future, right? So, this is like to me an incredible privilege that we can kind of work towards this this north star and have it all make sense.

The 3 AI-designed molecules

Hosts: And you've you've actually launched three AI design molecules. Is that right?

Alex: That's right. Yeah. So, you know, part of our business is not just making blended scents, but we actually build totally new molecules. Um, the What does that even smell like? Welcome to come in into our lab in New York and smell them. I mean, it's like, you know, if you look at a painting, it's made of a whole bunch of colors and those colors can be used very judiciously to create all kinds of feelings. So, looking at like a new color is kind of weird. It's like, have I seen that? Have you not seen that? You know, um, the answer is like, no, you haven't seen it in these cases. like they're actually totally new smells. Um, the one that I like the most, glossine, so it has a nice like kind of purple fruit floral smell. It's very kind of just pleasant. What was amazing about it is you put that in a fragrance and it lasts an hour longer like instantly. Wow. So, we we've got all these kind of interesting side benefits with some of the the molecules that we've created. Um, and the customers for these are just they're the really big companies that can make use of proprietary molecules. So you have to be a very very big company to be able to make use of this kind of a product. So you know you probably won't buy a bottle of this stuff um anytime soon. It's kind of a it's a component that goes into you know really large global products.

Hosts: Yeah. Yeah. That is interesting. So um are major brands using these yet or are we at a point where uh you've gotten some interest?

Are major brands using these?

Alex: Yeah. So, you can go to stores. I I I can't tell you exactly which ones and which brands because we we kind of we want to be in the background, but you can go to major stores you probably buy stuff in and you can buy products with fragrance that was made by Oldactory Intelligence. So, it's it's not theoretical. It's working. The scents are beautiful. They're safe. They are they they do the job. They're affordable for the customers that that buy them and ultimately build a product for their consumers. So, this isn't um you know, if we talked a year ago, I'd be like, "Ah, we probably can do this." And um and now it's like, "No, we definitely can do it." And we we've got to do a whole lot more of it. Um because it's it's working and it's really beautiful.

Hosts: That's amazing. Well, you know, the the fragrance industry is dominated by what, four massive companies mostly. Yeah. Have Have you gotten their attention yet or are they uh I know you should have some they should have one on your podcast.

Disrupting the $62B fragrance industry

Alex: Um uh I think I think the short answer is yeah. I mean it's not so fragrance is super important. It's the one reason why people keep coming back to buy most products. Usually not the first reason people buy it, but it's a it's almost always the reason people come back. So, it's a very very powerful part of of our economy, but it's very secretive and actually quite small. And so, um you know, when we started out, I would say, uh the vibe generally was like, isn't that cute? Um and, um I think things are changing. Look, what we focus on mostly is a part of the market that the fragrance industry has historically ignored, and those are folks that are starting out, right? folks that want to create fragrance but actually don't have a way to do it. Right? So like Cory and Grant want to create a fragrance. How do you even start? If you Google for it, you might actually just find us as the solution. Um right.

Hosts: Right.

Alex: So that that's there's just there's there's an unserved customer that wants to get started but doesn't know how. And by kind of combining all of the data, the algorithms, the operations, and the artistry like perfumers have helped us create this product in a very material way, anybody can get started now. And so that's that's we're not really competing against anybody. And I think even the major fragrance houses know that and they say, we're actually not able to serve these smaller customers because of how we've been historically set up. They've been doing things this way for about 300 years and more and more and more over time specialized on serving bigger and bigger customers. Makes complete business sense. Meanwhile, indie brands are the fastest growing segment ever, right? So like more personalization, people's circle of trust is kind of getting smaller. I mean even for buying products, right? And uh these are the folks that need some help and so that's what we focus on.

Hosts: Um what is like the form factor that people are would use like are is this like they're going to launch perfumes, candles, is there other options?

Alex: Yeah, right now we focus on uh ethanolbased spray fragrance and the simple way to remember is perfume, right? So there's subtypes of perfume like a body mist or a room spray or a hairspray. They're all basically different form factors of of a of perfume um and different dilutions delivery mechanisms for the scent. Yeah, exactly. So, the bottles will look different, but they're like under the hood, it's the same. So, that's what we really focus on right now, and there's plenty of business for us doing just that. Uh, but there's lots of other form factors that people would want. We call them applications. So, you know, people might want to launch a candle or a read diffuser or, you know, we could name another 10 of them. Scratch and sniff book. Yeah, scratch and sniff book. Playing cards, photographs with your custom. So, there's plenty of stuff that we're going to do. Um, but we're keeping it really simple. So, we design beautiful fragrances that uh are are kind of in the perfume form factor. Uh, and we're kind we want to build up trust and build up experience and momentum in that and then we'll we'll widen it over time.

The ultimate goal: Detecting disease through smell

Hosts: Well, I'd like to talk a little bit about, you know, your your end goal here. You know, I know and we've talked about this a little bit already that that dogs can smell certain types of cancers and Parkinson's. Um, how far out are we from a time when a computer can do that?

Alex: Boy, so I think the way I think about it is how far out are we for the average person being able to do that. So, as with most technologies, the future is here. It's just unevenly distributed. And the future is here and it is unevenly distributed. So if you wanted to go out and smell a disease in one way, shape or form and you had a laboratory like we do, you could do it. The issue is you couldn't give it to everybody.

Hosts: Yeah.

Alex: And you wouldn't today you wouldn't necessarily know what about that smell is making me believe or making my system, my algorithm believe that this disease is present or is not present. So we're missing some things. The first thing that we're missing that's most important is a lot of data. So again, I I think it's good to go back to an analogy and think about a time when doctors didn't know that looking at the molecules inside of blood was valuable because that was true a 100 years ago, maybe even to the 40s. I've got a bunch of blood, whatever. Right? Like I don't know if there's anything interesting in it. And blood is blood.

Hosts: Yeah, they were whatever. Not that long ago before that, they were bleeding. Exactly. I was like, "All right, we got too much blood. Get rid of it."

Alex: Um, you got too much blood. That's what's wrong. So, there was there was a study that was run, a very profound study called the Framingham Heart Study. And it's named after the town of Framingham, Massachusetts. And what they did is they looked at heart disease of basically everybody in the town. and they just tracked and measured the things that that they knew at the time um or uh you know were indicative of heart disease and then they did a smart thing which is they just collected as much data as they could even if they didn't know what to do with it at the time. One of those things was they took blood samples and they froze them and when they went back much later and they looked at that blood and they knew who had heart disease, who didn't have heart disease, they found a few things over time. They found that this thing called cholesterol wasn't actually that great for your heart. In fact, a subtype of cholesterol was was the worst. And they found that there was this molecule, you know, this class of molecules called statins that actually were really good for preventing heart disease. And they found a whole host of other things. It it's called bioprospecting. People still do it today. So the the kind of the big version of this that's happening in the UK is called the UK bio bank. In the US is called All of Us. And the idea is is pretty simple. I mean, the scientists like me like to guss it up with different words, but it's like, uh, let's go fishing. Let's collect everything that we can possibly collect, and then maybe we can sort out something that's valuable after we do that for a long while.

Why we need a "Framingham Study" for scent

Alex (continuing): Scent could become the new breath, but we need to do some bioring. We need a Framingham study equivalent for scent. That hasn't been done. And it's reasonable because the cost of analyzing a scent sample or even in some ways how to even do it in the first place. The cost is high and how to do it is not that well established. We've largely fixed the cost problem by building this company and kind of solving the problems we've had to solve. And I think over time we'll solve the sampling problem. And what's missing frankly is a nation state. That's the level. um or um an extremely wealthy individual or group of individuals to say we want to do better than blood. We don't want to have to stick a needle in young people or in old people and we also want our answers almost instantly and so we have to use not the molecules circulating in the liquids inside of us but the molecules that are always escaping through our skin. We want to we want to tap into that. We know that air is data and we just call that smell.

"Air is data" - The missing data set

Alex (continuing): That's the tag that we use for the data that's in the air that we detect. Why don't we go start to collect a database of that? So that's the real missing piece. Now once you know what you're looking for and you start to correlate the data that we constantly exhaust with disease or with health states, you have to build a device which anybody can have and hold that can tap into that. And you actually probably use different technologies for collecting the gold truth data versus the stuff that's pervasively available. So, we're probably at the state now where we can do a Framingham study for scent. We're not at the state technologically where anybody can have a device the size of a coffee cup or a cell phone that can actually detect that. You you'd still have to go into the laboratory. We have devices that are pretty good, but we don't know and they're about the size of two shoe boxes, but we don't know because we don't haven't done the data set collection. We don't know if they're good enough for disease detection. So there's still more work to be done, right?

Hosts: Yeah. Do do you think there's any limit to what you could learn about like the let's say like just the human body for example with with smell like...

What are the limits of smell?

Alex: Boy I mean here here's what here's what I've learned about smell over working on it and working on it and and thinking about it for a while which is what's on the inside gets to the outside. And there's a reason why a big chunk of the middle of our face is dedicated to analyzing it, right? Like we have these noses that don't seem to be getting smaller over evolutionary time. They're not like appendices. We need them, right? They're our private spectrometers. And there's a reason why some things smell tasty, right? So the things that smell delicious, we're detecting the molecules from the, you know, roasting meat or ripe fruit, the molecules that smell delicious are directly derived from the nutrition inside of that thing. So it's a it's a causally downstream signal of why eat that fruit, right? So it's the same with human disease, right? There's processes happening on the inside and those mo that those molecular processes, biological, metabolic, enzyatic processes, they're private inside of our skin because those molecules can't fly into the air. Proteins are too big to be smelled and to fly through the air. But those processes produce exhaust, right? They they produce they off gas and and they they produce molecules that are small enough to get into the air and they produce lots of molecules in specific ratios and that is what smell is. So to answer your question, what's the ceiling? Um we don't know until we look but right now I can't see the ceiling.

Hosts: Wow. Yeah. Interesting. So let's talk about um the other sensors that we have um and how we could potentially uh digitize those, right? So we have obviously we've digitized sights, we've digitized sound. Um now we've working on smell. What what does that leave? Taste and touch. Yeah. How would we do that?

What's left to digitize? Touch and taste

Alex: Um so touch is interesting. So some of my um mentors, advisers, colleagues worked at a company called Control Labs and they digitized grasping. So they digitized muscular activity. So they uh converted you know the intention to move the hand into a digital signal. If you saw recently Meta launched this armband that kind of digitizes your that's them right. So they were bought by Meta. So it's becoming a product, right? Um and I'm sure there'll be gloves and skin suits or whatever in the future that actually can play Touch back to us. Who knows, right? Um, I'm sure some very, very bright, motivated people are going to figure it out because it's like on the road to fully immersive virtual reality. And then taste. Um, man, if you can get smell right, you're you're going a long way to flavor. So, not what's happening on the tongue, but just the flavor experience. Um, but beyond how to do that on the tongue, I don't know.

The hardest sense: Can we digitize a story?

Alex (continuing): Um what in terms of frontiers though what I'm just fascinated with is can we digitize like in a way where we can think about it quantitatively. Can we digitize a story? Because what I what I've noticed in doing science and in building companies is that the thing that really binds people together is uh is a story. So, I can't show people the future that we're building. It's not physically real, but I can tell a story of what I think is possible. And I can explain why why I think now is the time to do it. The only reality of that is a story. And I think it's incredible that people can choose to believe or disbelieve um completely immaterial things but yet can organize huge numbers of people to do the extraordinary. And what's very strange to me is we're in this era of LLMs and I think the magnitude of of what we're talking about now is masked by the ability to have a machine create coherent sentences and paragraphs of English language and of other languages. I have yet to read a story written by one of these machines. It will happen. I I think right I mean there's no reason to believe it's not possible. But there's something different between language and a story. There's a quantum leap between grammatical correctness and something that causes you to dedicate your life to a mission. And so like somewhere along the line, I received the story of digitizing your sense of smell. I didn't invent it, right? Like people have been thinking about this forever, but it completely got me. I got completely oneshotted by this story. And now like I live it and breathe it and I'm I'm happy to, right? I think that's astounding. Like nobody ever showed me digital smell, but yet I I'm I'm like working in a tradition that goes back a century or more and I never met the people that came up with the thing in the the story in the first place. Like how absolutely extraordinary is it to have a society bound together by such a thing? I it's nothing to do with what we've been talking about, but I'm just astounded by the power of story sometimes.

Hosts: Well, you know, something that that I do that that reminds me of this, the idea of smelling a story and the idea of of all of this. Um, I enjoy taking song lyrics and feeding them to image models as possible and seeing what they come up with and seeing just what comes out. I'll do it with poetry. I'll take a, you know, some classic poetry and drop it in and see what it creates. No other instruction, just here are the lyrics, go. And uh I I really enjoy playing with that and looking to see just kind of how it translates this into that. And it makes me think a lot about what you're what you're saying here. And I I feel like there is an area of u that current artificial intelligence is is lacking in that it it needs these other senses. it needs experiential data of some type, you know, like and and I've used this example before on here, so it's probably familiar to people, but uh the idea that how can an how can we teach an AI to understand what a spring morning feels like?

Alex: It's got to be in the data set. That's the short answer. The actual experience of a spring morning is not in the data set, right?

Hosts: Yeah. Well, do you think uh do you think that embodied intelligence is key to AGI? And I guess well taking that one step further. Do you think smell is key to five minutes? And I don't know we're going to be able to get into that. Try to tackle that here.

Hot take: AI, AGI, and S-curves

Alex: Here's what I think. Um all technology here to date. And I don't think that what we're seeing right now is any different. Progresses on a on an S-shaped curve where it's doesn't get better faster really at all. And then all of a sudden there's something that changes and it gets better really fast and then it saturates and it basically plateaus. um everything is like that up until now. So internal combustion engines generating light via a candle, generating light via natural gas, generating light via electricity. Now those S- curves stack, right? So candles, there's actually technological breakthroughs in candles while natural gas was coming online. And candles were straight up better for like a decade because people were like improving candle geometry. Like you don't think about candles as tech, but it was straight up tech back in the 1800s. But those S-curves stack, right? And that creates an in when you stack them really well, it creates an exponential in some capability, like the amount of light you can produce for a dollar, right? But it requires a bunch of different breakthroughs that each have their own S-curves. Text generation has its own scurve using transformer-based models. So, we call those LLM. I think we're getting close to the elbow and plateauing off because the the limiting factor is the internet, right? Like you're out of data. you're out of the internet. It's gone. We've digested it all. Uh and I don't think that we've seen the amount of crazy progress in the past year that we saw say, you know, year five ago to year four ago. Like that was wild progress. And now we're things are getting better and we're adding new features, but we're adding features to products. We're not, you know, we're not growing some capability nearly as fast as we were before. This is my like hot take, which is um Yeah. Yeah. uh language models are great and all, but like when we talk about progress in AI in general, we're actually talking about dozens of different technologies, right? And so what I'm seeing is kind of a is a is a a bit of a smok and mirrors or masking game, which is like, oh, the progress is the same rate. No, no, no, no. Uh progress on video generation is a different scurve. Progress on image generation is a different scurve. Now, you can build products that integrate all this stuff. Oh my gosh, can you create so much value in society by combining these things to products? It's not the same as technological progress, right? So, if what you want is to figure out when your AI god will wake up, I don't agree with that. I don't think that is a thing. Um, I think what we have is a new form of steam turbine engine, but for mental work, and that thing has its own S-curve. It's a piece of technology. Now, let's go put it to work and do some awesome stuff, right?

Hosts: And so what and do you think smell will be one of those?

Where smell's S-curve is heading

Alex: smell is on an add and we're at the very bottom of this and we're starting to take off but um that's what we're committed to is like we want to contribute to society in the long arc of human progress by moving on one of those scurves and it's by the way the oldest sense that evolution has invented. It's very emotionally powerful. Um, and nobody else is really working on it, uh, in the way that we are. Not to diminish the amazing science that's come before and is operating currently. But like the way we're going after this is kind of in the in the modern AI company way, which is let's go get a ton of data. Let's build a great business model behind it that creates a flywheel and let's actually like call our shot. like let's let's have a goal that's worthy of of of of reaching it and then make sure that all the steps along the way make sense and then react to what we learn along the way. Um but we are we are dedicated to moving up that scurve of olfactory intelligence. That's what we're here for.

Hosts: Awesome. That's awesome. Well, Alex, how can listeners experience this right now? What's the best place to go to learn more?

How to experience Osmo right now

Alex: So, uh they can follow OSMO on Twitter or LinkedIn. Um and we're going to have some great announcements soon. Um, but we've got a private beta program. So, if you Google around for how to create scent uh with Osmo Studio, I think you'll be able to find that. Uh, and then stay tuned for uh not too long in the future when we have an amazing tool that anybody can use to create their own sense using allactory intelligence.

Closing & farewell

Hosts: That is awesome. Very cool. Well, thanks so much for joining us today, Alex. Please go check out Osmo. You're going to be fascinated with what they have. Uh, I'd like to thank everyone for watching and listening today. Okay, we just explored something that sounds like pure science fiction, honestly, in some ways. And the idea that we're teaching computers to smell, but it's real. It's happening now, and Alex here is doing it. We hope you enjoyed today's show. If you don't already, please like, subscribe so we can continue to bring fascinating conversations like this one to you. Join more than a half million others today who read the Neuron AI newsletter every morning. And u on that note, till next time, farewell, humans.