Ever feel like you're watching everyone else build apps with AI while you're still figuring out where to click? You're not alone. The gap between "I've heard of coding agents" and "I actually use one" feels massive—until it isn't.

We just wrapped a two-hour livestream with Alexander Embiricos, OpenAI's product lead on Codex, and walked away with a complete playbook for going from curious observer to confident AI-assisted developer. No prior coding experience required.

What follows is everything we learned: how Codex works under the hood, the exact workflows OpenAI engineers use internally, and practical strategies for anyone who's been intimidated by terminals, IDEs, or the general mystique of "vibe coding."

Fair warning: this is a long one. Grab coffee. Maybe two.

Also, shout out to Alexander for spending two whole hours with us! You're a legend for that one, Alexander!

The TL;DR; if you only have 3 mins, read this...

IMO, the most important part of the stream happened right towards the end: Alexander introduced a concept he calls the "Inner and Outer Loop" of AI development. It’s not just about asking a chatbot to write a script; it’s about integrating AI into the entire lifecycle of software.

- The Inner Loop (1:52:01): This is the actual coding. You configure Codex with an agents.md file (which tells the AI how you like to code, e.g., "use tabs, not spaces") and run your tests.

- The Outer Loop (1:54:13): This is the management. Alexander showed how they use Codex to triage tickets in Linear and perform a "pre-review" on Pull Requests before a human ever looks at them.

- The Automation (1:54:35): Finally, you script the AI to handle recurring nightmares, like checking Sentry logs for crashes related specifically to your recent code commits.

THE NEW MODEL: We also dug into GPT-5.1 Codex Max, which is now available in the API. Alexander shared when he uses each of the main models, and for what:

- Low Reasoning: Use this for "Vibe Coding"—quick, interactive chats where you need speed.

- High/X-High Reasoning: Use this for "Agentic" tasks. Alexander described setting Codex to "High," walking away for 20 minutes, and coming back to a fully refactored codebase.

WHY IT MATTERS: The results speak for themselves. OpenAI’s internal usage of Codex spiked from <50% to >90% this year, and they saw a 70% increase in Pull Requests. They even built the entire Sora Android app in just 18 days using this workflow.

TOOLS TO TRY: Alexander’s personal stack includes VS Code (obviously), Cursor, Ghostty (for terminal), and Atlas (OpenAI’s browser).

THE RUMOR MILL: We tried to press him on whether OpenAI is doing a "12 Days of Christmas" launch event this year. His response? A very suspicious, very playful "I don't know." (We’re taking that as a yes).

OUR FAVORITE PART (1:41:47): The Three Phases of AI Adoption. Alexander shared a framework that stuck with us. He describes AI adoption as happening in three phases:

- Phase 1: Open-Ended Power. This is where we are today. Incredibly powerful tools exposed through simple interfaces. You can ask for anything. The onus is on you to figure out what to ask and how to prompt effectively.

- "This is a really fun time for tinkerers," Alexander said. But it's also hard. You need to stay online, read about stuff, experiment on your own time.

- Phase 2: Tinkerers Help Non-Tinkerers. This phase is just beginning. The people who figure things out create configurations, templates, and skills that others can use without understanding the details.

- Think of it like the early web: at first you needed to know HTML. Then WYSIWYG editors let anyone create pages. The capability was the same; the accessibility expanded.

- Phase 3: AI Just Works. The final stage: you don't think about "using AI" anymore. It's simply how software works. Tab completion in your code editor is an early example. You're not consciously "prompting an AI"—you're typing, and predictions appear. You accept or reject them without switching modes.

- The goal for Codex (and AI tools generally) is to reach this phase: intelligent assistance embedded so deeply into workflows that it becomes invisible.

"We need to be at this phase where you don't actually have to think about using AI," Alexander said. "AI just helps you." Love that!

The Live Stream Itself...

Timestamps for Our Top Takeaways

If you only have a few minutes or want to watch the key moments from the livestream, here are our favorite parts (we'll dive into all of them below in more detail).

The Codex Vision & GPT-5.1 Codex Max

- (09:29) Redefining the "Coding Agent" as a Teammate: Alexander (Product Lead) defines Codex not just as a tool to write code, but as a teammate that works everywhere (IDE, CLI, cloud, phone). The goal is to move beyond the 30% of time engineers spend writing code to cover the ideation, planning, validation, security, and deployment phases.

- (11:09) The "Intern" Analogy for Current Agents: Most current coding agents are like interns who are good at writing code but "refuse to check Slack" or validate their work. The goal for Codex is to close the loop—connecting to tools to validate, review, and monitor code after it is written.

- (12:31) Launch of GPT-5.1 Codex Max: Alexander confirms the release of GPT-5.1 Codex Max to the API. It is significantly smarter at coding tasks and more token-efficient than previous models.

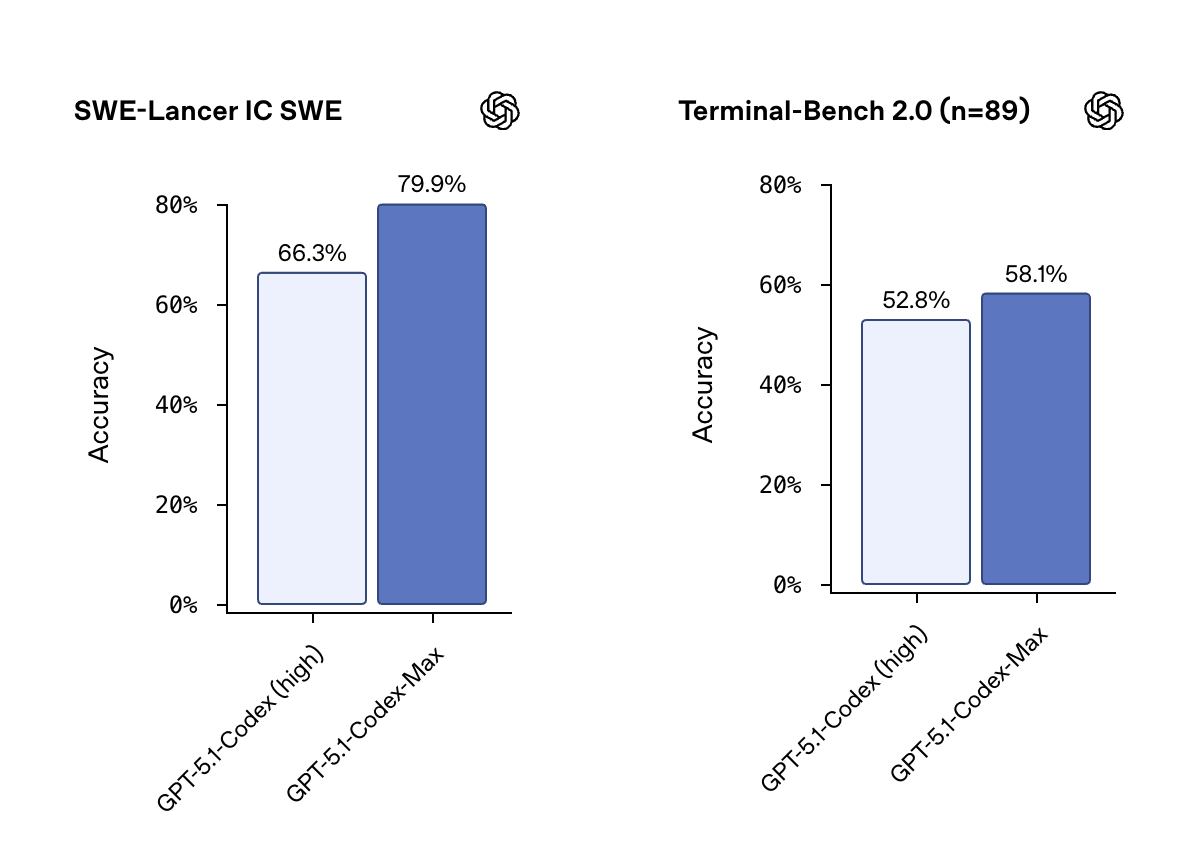

- (14:12) "Lancer" and "Terminal Bench" Evals: OpenAI uses specific evaluations like "Lancer" (freelance tasks) and "Terminal Bench" (complex command line tasks) to grade models. The jump from Codex to Codex Max on these benchmarks is significant.

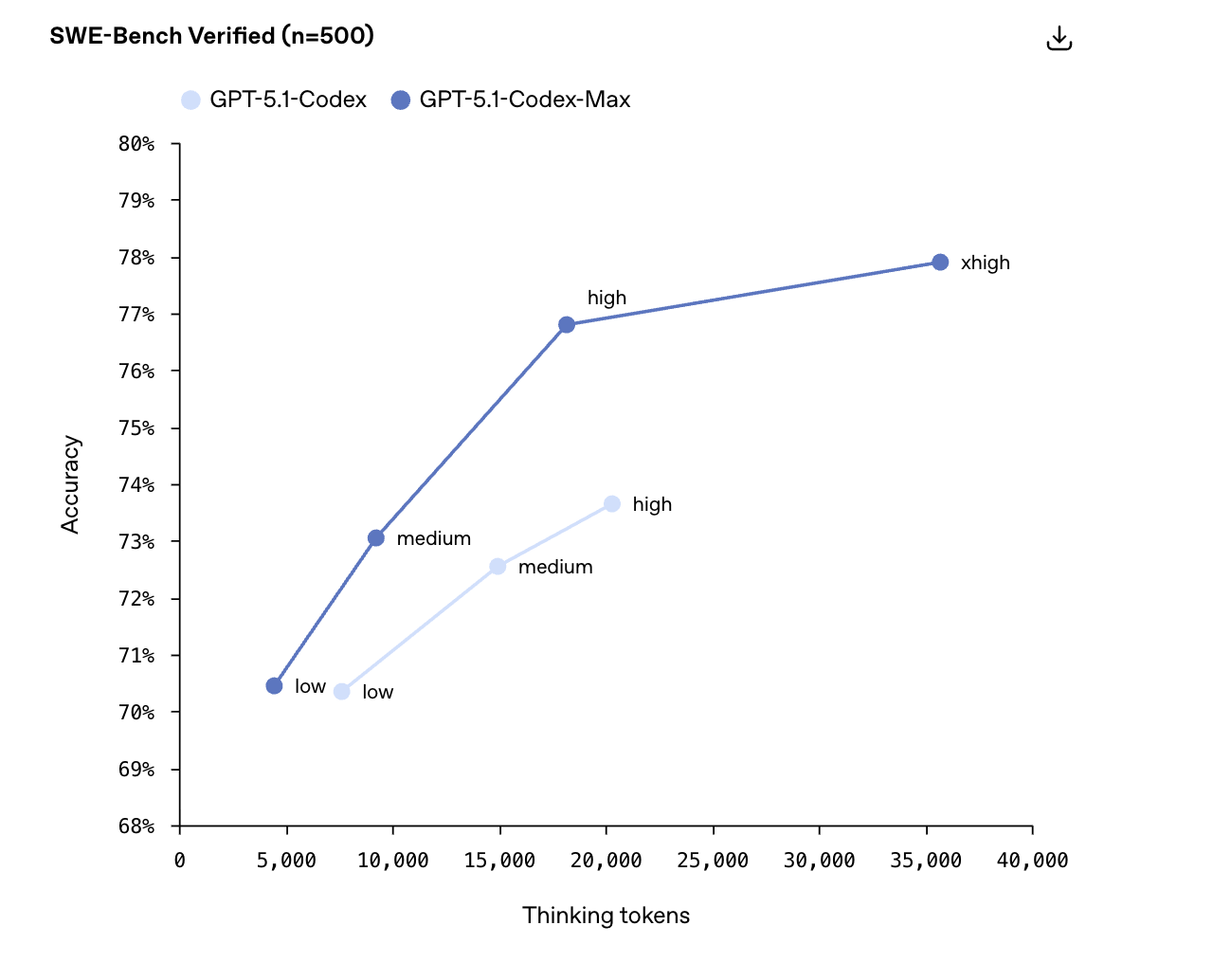

- (16:26) The Efficiency vs. Thinking Graph: Alexander reveals a critical internal graph. The new model can achieve the same score as previous models with drastically fewer "thinking tokens" (making it faster/cheaper), or achieve much higher scores when allowed to "think" for longer periods (high reasoning).

- (19:33) Building the Harness vs. The Model: A key differentiator for OpenAI is that they build the "harness" (the environment the agent runs in) alongside the model. This allows for specialized features like "compaction" because the model is trained specifically to work within that specific harness.

Actionable Workflows: agents.md & plans.md

- (28:50) "Compaction" for Long-Running Tasks: To solve the context window limit on massive tasks, Codex uses "compaction." The model is trained to summarize and prepare its state to run again in a fresh context window, allowing it to work indefinitely on long tasks without losing the thread.

- (32:52) The agents.md Configuration File: You can create a file named agents.md (plural and generic by design) in your repository. Codex reads this before every interaction to understand your specific style, preferences (e.g., "always sound like a pirate"), or architectural constraints.

- (1:05:32) The plans.md Strategy for Complex Tasks: For hard tasks, don't just prompt for code. Ask Codex to: "First, write a plan in plans.md explaining how you think we should do this." This allows you to negotiate the architecture with the AI before it writes a single line of code.

- (1:08:32) The "Aaron" Plan Template: An OpenAI engineer named Aaron uses a robust template for plans.md that requires the agent to include milestones, design decisions, self-negotiation steps, and to-dos. This structures the agent's thinking process for better reliability.

- (1:11:53) Combining agents.md and plans.md: A pro workflow is to add a rule in agents.md that says: "When writing complex features or significant refactors, use the plans.md approach to do the implementation." This automates the best-practice workflow.

Internal OpenAI Case Studies & "Vibe Coding"

- (1:10:32) The Sora Android App Story: OpenAI built the entire Sora Android app in just 18 days with 4 engineers. They did this by having Codex read the existing iOS repository and the Android codebase simultaneously, planning chunks of work, and porting features over rapidly.

- (1:13:29) The Linear Integration Workflow: Alexander demos a real workflow where he files a ticket in Linear (project management tool), assigns it to Codex, and Codex automatically picks it up, writes the code, and opens a Pull Request (PR) for human review.

- (1:14:49) The Slack "Let Me Codex That For You" Workflow: In OpenAI internal Slack, engineers can tag @Codex in a thread about a bug. Codex investigates, runs tests, and replies with a link to a PR fixing the issue within minutes.

- (1:16:08) Terminal as a Conversation: Alexander uses the terminal command codex to ask natural language questions about the repo (e.g., "are there worktrees for this repo?") instead of remembering complex Git commands.

- (1:21:27) "Best of N" Strategy: For difficult tasks, OpenAI uses a "Best of N" approach—running Codex 4 times on the same prompt to generate 4 different architectural approaches, then reviewing them to pick the best path before finalizing the code.

- (1:29:41) 70% Productivity Increase: During a specific period of aggressive internal adoption (moving from <50% to >90% usage among technical staff), OpenAI saw engineering productivity (measured by PRs per time period) jump by roughly 70%.

- (1:30:19) The "Atlas" Multiplier: A project called "Atlas" reduced a workload that previously took 3 engineers 3 weeks down to 1 engineer 1 week by utilizing Codex effectively.

Security, Review, and Deployment

- (1:33:38) Automated Code Review: You can configure Codex to review every PR submitted to GitHub. To avoid "bot fatigue," they trained the model to have a very low false-positive rate—it only flags issues if they are critical/real problems.

- (1:36:42) Project Ardvark (Beta): A new security-specific tool (Ardvark) uses Codex to identify security vulnerabilities, attempt to reproduce them to prove they are real, write a fix, and then verify the fix works.

- (1:38:17) The "Vibe Coding" vs. Engineering Divide: For "vibe coding" (prototypes), you can just deploy next.js projects to Vercel without reading the code. For "real engineering," you must use typed languages (Rust/TypeScript), modular architecture, and automated tests to verify the AI's output.

Philosophy of AI & Future Forecasts

- (44:23) The "Assembly" Analogy: Using AI isn't "brain rot"; it's an abstraction layer. Just as most devs don't write Assembly or C anymore because higher-level languages exist, AI is the next layer of abstraction that allows engineers to focus on higher-level problems.

- (46:14) "Lead with AI, Catch Up with Knowledge": Alexander suggests a new learning model: You can now aggressively expand your domain by building things beyond your current knowledge using AI, and then fill in the knowledge gaps "just in time" as you debug or refine the project.

- (1:42:31) The Three Phases of AI Adoption:

- Open-Ended/Tinkering: Powerful but requires user effort/prompting (Current state).

- Configuration/Scaling: "Tinkerers" set up configurations (skills/agents) so the rest of the team can use them easily.

- Invisible/Automatic: AI acts as a teammate that helps without being asked (e.g., auto-reviewing PRs, auto-fixing bugs).

- (1:49:02) "Skills" vs. "Connectors":

- Connectors: Give the AI access to a tool (e.g., connect to Sentry).

- Skills: A set of instructions on how to use the tool to create value (e.g., "Find crashes related to my recent commits and plan a fix").

- (1:50:20) How to get setup with Codex:

- Step 1: Set it up in your IDE.

- Step 2: Test it out.

- Step 3: Configure.

- Inner dev loop: What does Codex know about you? (set this up in agents.md, or skills.md, which are incoming).

- Outer dev loop:Where are tasks tracked? What do you do after you pull a request? (handle this in agents.md or skills.md).

- Automation: Things you do all the time? Automate them via the Codex SDK.

Now let's dive into all of that in more detail.

What Is Codex, Actually?

Let's start with the basics, because even "basic" gets confusing in AI.

Codex is OpenAI's coding agent. Not a chatbot that happens to know code—an actual agent that can use your computer, navigate your files, run commands, and write (or fix) code on your behalf.

The key word is agent. When you ask ChatGPT to write code, it gives you text you then copy somewhere. When you ask Codex to write code, it actually does the work: creates the files, runs the tests, validates the changes (09:29).

"The goal is to have Codex feel like a teammate that works with you everywhere you work," Alexander explained. "In your IDE, in your terminal, in the cloud, on your phone."

Currently, the most popular way to use Codex is through a VS Code extension (or Cursor, if that's your IDE of choice). You install it, connect your account, and suddenly you've got an AI collaborator sitting in your editor.

You can get started with Codex on OpenAI's official page or check out the Codex CLI on GitHub.

The New Model: GPT 5.1 Codex Max

Right before our livestream, OpenAI shipped GPT 5.1 Codex Max to the API with the same pricing and rate limits as GPT-5 (12:31). This matters because it's specifically trained for coding tasks—and the benchmarks are wild.

Alexander shared two charts that tell the story:

Chart 1: Raw Performance (14:12). On evaluations like SWE-Lancer (real freelance coding tasks) and Terminal Bench (terminal-based challenges), Codex Max significantly outperforms previous models. We're talking about a noticeable jump at the high end of the performance curve—the kind of improvement that usually takes multiple model generations.

Chart 2: Speed + Intelligence (16:26). This one's more interesting. The x-axis shows "thinking tokens"—essentially, how long the model spends reasoning before acting. The y-axis shows performance scores.

The key insight: Codex Max achieves similar scores with far fewer thinking tokens. Translation? It's not just smarter—it's faster. You get better results without waiting as long.

"I use Codex at low reasoning most of the time," Alexander admitted. The only exceptions: tasks he knows are genuinely hard, or situations where he's stepping away from his computer and doesn't mind the model taking its time.

Understanding the Harness: How Codex Actually Works

Here's where things get technical—but stick with it, because understanding this makes everything else click.

When you send a prompt to Codex, the model doesn't just see your question. It receives a whole package:

- Your prompt ("Fix the jump animation")

- System instructions (what it's allowed to do, how to behave)

- Available tools (commands it can run, files it can access)

- Context about your project (the code it can see)

This package is called the harness (19:33). And here's the cool part: OpenAI's harness is completely open source.

Check it out on GitHub—you can read the system prompts, tools, and everything the model receives.

"Any of you can go read it," Alexander said. "It contains all the tools and prompts that the model gets."

Why does this matter? Because the Codex team trains the model and builds the harness together. They're optimized to work as a unit. Alexander compared it to a sports car: incredibly good at its specific purpose, maybe less generalizable than a sedan.

One fascinating detail: the system prompts for GPT-5.1 Codex Max are much shorter than for standard GPT-5. The specialized model doesn't need as much instruction—it already knows how to operate in a coding environment.

Your First Codex Session: A Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Alright, let's get practical. Here's exactly how to go from zero to running Codex:

Step 1: Pick Your IDE

You'll need an IDE (Integrated Development Environment)—fancy term for "the app where you write code." Alexander recommends:

- VS Code: Free, widely used, easiest to find the Codex extension

- Cursor: VS Code fork with AI features baked in

- JetBrains IDEs (PyCharm, IntelliJ): Great for Python/Java developers

Download VS Code here or Cursor here.

P.S: You'll also need to set up Github. If you've never done that before, watch this video to set it up and this video to work with it via VS Code (we hear this video's a good alt to the first one if you're on Mac!).

Step 2: Install the Codex Extension

In VS Code, this is straightforward—go to Extensions, search "Codex," install.

In Cursor, it's trickier. The extensions menu is buried (Alexander diplomatically noted this, gracefully defending Grant's total noob moment of not being able to find the dropdown; thanks again Alexander!). Look for a dropdown arrow near the extensions icon. Click Codex to find and install it.

Step 3: Sign In

Click the login button in the Codex panel. You'll then authenticate with your ChatGPT account. Codex is included in Plus and Pro plans, as well as Business and Enterprise.

Step 4: Start a Conversation

With Codex open and a folder loaded, you can just... ask for things.

Simple example:

"How do I play this game?"

Codex will figure out what commands to run (maybe npm install then npm start), execute them, and give you an answer.

Real example from the stream:

Grant asked Codex to "Make a joke site about cats that write code." Within minutes, Codex had created three files (index.html, style.css, script.js) and built a working landing page with animated elements and cat-themed coding humor (screenshot of the final site at the end!)

That's the vibe coding experience in a nutshell: describe what you want, watch it happen.

The Sandbox: Why Codex Asks Permission

During the demo, something interesting happened. When Codex tried to open a browser window, it paused and asked for approval first.

This is the sandbox—Codex's security system.

"Launching your browser is a very powerful action," Alexander explained. "We've decided that the agent shouldn't just launch your browser to whatever site it wants without you first confirming."

You can approve once, or approve always for certain actions. The sandbox exists to prevent a coding agent from doing something destructive—like, say, deleting your files or sending emails—without your knowledge.

For experienced developers, this might feel limiting. For beginners worried about AI running amok on their computer, it's reassurance.

agents.md: Teaching Codex Your Preferences

Here's where Codex starts feeling less like a tool and more like a teammate.

Every project can include a file called agents.md (32:52). This is a configuration file that tells Codex how you want it to behave—and it persists across sessions.

The agents.md standard is documented in the Codex CLI repo—and multiple AI coding tools now support it (here's the OpenAI agents.md repo).

Alexander demoed a silly example: adding "sound like a pirate" to the agents.md file. After that, every response came with pirate flair ("Ahoy! I'd be sailing through yer code...").

The real use cases are more practical:

- Code style preferences: "Use two spaces for indentation, not tabs"

- Framework choices: "This project uses React with TypeScript"

- Testing requirements: "Always run npm test before confirming changes"

- Architectural patterns: "Follow our internal API structure documented in /docs/architecture.md"

The coolest part? Multiple coding agents support agents.md—not just Codex. Google's Gemini and other tools have adopted the same standard. So your preferences travel with your project, regardless of which AI you're using.

"We intentionally made it generic and plural," Alexander said. "We wanted to invite everyone to use it."

Plan.md: The Secret Weapon for Complex Tasks

For simple requests, you can just tell Codex what you want. For complex tasks, you want a plan first.

Enter plan.md—a workflow where you collaborate with Codex on what to build before letting it loose to build it.

Read more about planning workflows in the Codex CLI documentation.

Here's the basic flow:

- Ask for a plan: "Let's work on adding moons to the solar system app. First, write a plan in plan.md explaining how you think we should do this."

- Review and iterate: Codex produces a plan. You read it, suggest changes. Maybe: "Don't add separate controls for moons—just populate them by default."

- Execute: "Do the plan."

This two-step process—plan, then execute—is how serious engineering gets done with AI. You're not just hoping the model does something sensible; you're collaborating on the approach before any code gets written.

Alexander mentioned that one engineer at OpenAI, Aaron Friel, has taken this to an extreme. His plan.md templates include sections for:

- Self-negotiable milestones

- Design decisions with rationale

- Specific formatting requirements

- To-do checkboxes for tracking progress

You don't need to start that sophisticated. "Just start easy," Alexander advised. "You don't need any of that."

But knowing the option exists matters. When your projects get complex enough that simple prompting fails, plan.md is waiting.

And, later in the stream, Grant suggested you could spin up two different versons of your project; one with the sophisticated plan.md, and one basic one. In case you want to do that, we share Aaron's full plan.md file at the end to copy pasta.

How OpenAI Actually Uses Codex (Internally)

This was the part of the conversation I found most valuable: seeing how the Codex team at OpenAI uses their own tool in production.

Example 1: The String That Was In The Wrong Place

Alexander wanted to move a status message from the top of a CLI output to the bottom. A tiny change, but one that required finding the right file, understanding the code structure, and making the edit without breaking anything.

His prompt:

"When I run /status, the string [X] shows up at the top of the output. Let's move it to the bottom so users don't have to read that immediately—it's extra info."

That was it. Codex figured out where the string was defined, understood the rendering logic, made the change, and then ran the test suite to validate the edit.

"I didn't write any of that code," Alexander confirmed. For this type of well-defined, testable change, human involvement is mostly oversight.

Example 2: Linear Integration

This one was wild. Alexander filed a ticket in Linear (a project management tool), assigned it to Codex, and... Codex picked it up.

The model read the ticket, understood the requirements, wrote the code, created a pull request on GitHub, and linked everything together. Human involvement: writing the ticket and reviewing the PR.

"Notice I actually wrote a bit more of a ticket than I would have in the past," Alexander noted. "Because I actually want the agent to understand what I want."

Learn more in the Codex–Linear integration docs.

Example 3: Slack Mentions

In OpenAI's Slack, engineers can now @ mention Codex directly.

The screenshot Alexander shared told a story:

- Engineer asks a debugging question in Slack

- Colleague shares a potential fix idea

- First engineer types: "@Codex can you try this?"

- Codex responds: "I'm on it"

- Eight minutes later, Codex posts a link to a completed PR

The second engineer even jumped back in: "Actually, I think we need to do this differently." Response: "@Codex can you change it to do that other way?"

It's the AI equivalent of "let me Google that for you"—except the AI actually does the work.

Example 4: Automated Code Review

Every pull request at OpenAI automatically gets reviewed by Codex.

The system was trained with a specific goal: low false positive rate. "We were like, hey, for now don't flag every single opinion you have about the code—just flag when you think it's a real problem."

This was a deliberate choice. OpenAI was worried engineers would hate bot criticism. Instead, they made the bot's feedback rare but meaningful. When Codex leaves a comment, it's worth reading.

The feedback mechanism is simple: thumbs up or thumbs down on each review comment. This trains the system to get better over time.

You can read more in the Codex GitHub code review integration docs.

Vibe Coding vs. Vibe Engineering: The Spectrum

Let's define some terms, because they keep coming up:

- Vibe Coding: You describe something you want ("make a website about cats"), AI builds it, you don't really look at the code. Perfect for prototypes, one-off tools, or learning experiments. If it breaks later, you might just rebuild from scratch.

- Vibe Engineering: You use AI extensively, but you're deeply involved in architecture, planning, testing, and review. The code ships to production. If it breaks later, you need to understand it well enough to fix it.

We asked Alexander about a debate we saw recently online: Is AI making us "lazy" coders (equivalent to brain rot)? Or is it making us all 10x engineers? Alexander argues it’s about "Vibe Engineering."

Alexander says the difference is about human involvement and intent.

"If you're building something that's going to be used by many people," Alexander explained, "you still want to understand the underlying systems. You still want to be an expert. The difference is that you're a massively accelerated expert."

For beginners just learning, Alexander's advice: follow your energy.

"Try building some project you have and see where you get stuck. Just use AI to build that project. Some things will be easier for you based on your personality—you can just pull that thread."

The cold start problem that traditionally plagued programming education? Largely solved. You can start building on day one and backfill knowledge as you need it.

So, putting that into a framework:

- For Prototypes: If you’re building a fun app (like the "Cat Coder" site they built live), you can just "vibe." You don't need to read every line of code.

- For Production: If you’re building the Sora Android App (which OpenAI built in just 18 days with 4 engineers), you need a different approach. You use plan.md files to negotiate the architecture with the AI before a single line of code is written.

The Sora Android App: 18 Days With 4 Engineers

This story deserves its own section because it illustrates what "AI-accelerated development" actually means at scale.

OpenAI needed an Android app for Sora (their video generation product). They already had an iOS app. Timeline: as fast as possible.

Result: 4 engineers, 18 days to a testable app. 28 days to full App Store launch.

The workflow:

- Open Codex with access to both the iOS codebase and the Android codebase

- For each feature chunk, ask Codex for a plan based on how iOS did it

- Iterate on the plan with the team

- Send Codex off to implement

- Review, test, repeat

"What used to take maybe three engineers three weeks is now one engineer one week," Alexander said.

This wasn't vibe coding—it was what Alexander calls vibe engineering. Humans very much in the loop, being thoughtful about architecture and quality, but radically accelerated by AI handling the mechanical coding work.

Is Learning to Code Still Worth It?

This question came up in the chat, and Alexander's answer was nuanced.

Short answer: Yes, absolutely.

Longer answer: What "learning to code" means is evolving.

"Most people don't need to know assembly today," Alexander pointed out. Once upon a time, that was essential knowledge. Then higher-level languages made it optional. Then frameworks abstracted away more. AI is another layer in this progression.

But the fundamentals still matter:

- Understanding data structures

- Knowing how systems connect

- Debugging when things break

- Making architectural decisions

"If you want to build something really meaningful, you still want to understand the underlying systems," Alexander said. "The difference is that you're a massively accelerated expert."

His mental model: think of AI as the most powerful abstraction layer yet. You don't need to hand-code everything, but you need to know enough to direct the system, catch mistakes, and handle edge cases.

The hybrid learning approach—building with AI while studying fundamentals—might actually be superior to traditional education. You get immediate hands-on experience while learning theory just-in-time as you encounter problems.

Three Barriers to AI Coding (And How to Overcome Them)

During the stream, Grant raised three specific challenges he's faced. Alexander's answers apply to anyone stuck in similar places.

Barrier 1: Getting Stuck in Loops

The problem: You're working with an AI coding tool and it gets confused. You ask it to fix something, it claims it fixed it, but it didn't. You point this out, it "fixes" it again. Loop continues.

The solution: Multiple parallel attempts + fresh starts.

"We tend to like doing something we call 'best of N,'" Alexander explained. Run Codex four times on the same task, in separate instances. Compare the outputs. Often you'll get one that works beautifully, another that's completely wrong, and two in between.

The key insight: if you see multiple different approaches, you understand the problem better. Then you can start fresh with much more specific instructions.

Also: "Create new chats aggressively if you find the agent getting stuck."

With newer models (especially GPT 5.1 Codex Max), Alexander noted he needs to start fresh much less often. The longer context understanding has improved significantly.

Barrier 2: Deploying to the Real World

The problem: You've vibe coded something amazing. How do you actually ship it?

The solution: It depends on what you're building. (1:39:25)

For quick prototypes (single-player tools, no user data): just deploy. Services like Vercel make it trivial to push a Next.js app live. If it breaks, you rebuild.

For serious production apps: you need the full engineering workflow. Planning, code review, testing, security audits. The AI accelerates each step but doesn't replace human oversight.

The middle ground gets interesting. "If you're asking users to upload data, then you've got to make sure you do right by them with security," Alexander said.

Check out the Vercel deployment guide for Next.js and the Vercel Next.js docs.

He brings it up in the context of "vibe coding" prototypes versus serious engineering. His advice is that for experimental, single-player tools without user data, you don't need a heavy process—you can just have Codex build a Next.js project and deploy it immediately to Vercel.

Barrier 3: Security Concerns

The problem: You're a coding noob. You don't know what security vulnerabilities look like. How do you avoid shipping something dangerous?

The solution: Automated code review + specialized security tools.

First, enable Codex's code review feature. Every PR you create will get reviewed for issues.

Second, OpenAI is building something called Aardvark—a tool specifically designed for security analysis. It's currently in beta, aimed at security engineers, but the capability will likely become more broadly available.

"Aardvark identifies issues, attempts to reproduce them, demonstrates that the issue is real, then sends Codex to fix it and tests that it's actually fixed," Alexander explained.

This feedback loop—find vulnerability, prove it, fix it, verify fix—is exactly what security teams do manually. Automating it makes secure coding accessible to non-experts.

Learn more in OpenAI's Aardvark security tool announcement.

Setting Up Your Development Environment: The Inner and Outer Loops

Alexander introduced a useful mental model for configuring Codex effectively.

The Inner Dev Loop

This is everything related to actually writing code:

- Does Codex know where your context files are?

- Does it understand your code style?

- Can it run tests?

- Is it configured for your language/framework?

Most of this goes in your agents.md file. Start minimal, add instructions when you notice problems.

The Outer Dev Loop

This is everything around writing code:

- Where do you track tasks? (Linear, Jira, GitHub Issues)

- Where do you brainstorm? (Notion, Google Docs, Slack)

- What happens after a PR? (Code review, CI/CD, deployment)

Setting up integrations (Linear, GitHub, Slack) enables Codex to participate in these workflows natively.

Automation

Once you've configured both loops, you can automate triggers:

- Every new ticket assigned to Codex → agent starts working

- Every PR created → automatic code review

- Every deployment failed → agent investigates logs

The Codex SDK enables building custom automations. It's essentially a programmatic interface to Codex's capabilities.

See the Codex SDK documentation for details, or install it from npm as @openai/codex-sdk.

Skills: An Experimental Feature Worth Watching

Near the end of the stream, Alexander showed something unreleased: skills.

Think of skills as reusable capability modules. Instead of writing the same instructions repeatedly, you define a skill once and invoke it by name.

Simple example:A skill that knows how to query OpenAI's job listings. Type /skills enable open_ai_jobs, then ask "Is the Codex team hiring?" and get a live answer pulled from their careers page.

Complex example: A Sentry integration skill that:

- Identifies crashes from the most recent release

- Filters to code you personally wrote

- Plans an investigation approach

- Proposes fixes

All of that logic—which APIs to call, how to interpret results, what format to return—lives in the skill definition. You invoke it with a simple command.

This is the bridge between open-ended prompting and fully automated workflows. Skills let tinkerers share their discoveries with less technical teammates.

"Someone on the team can figure out that this skill makes sense," Alexander explained, "and then make it available to other people or the broader team."

You can explore the Codex skills documentation for more.

Connectors vs. Skills: What's the Difference?

This came up during the Q&A, and the distinction is useful:

Connectors are ways to access external tools and data. Think of them as pipes: they connect Codex to Sentry, or Linear, or your internal APIs.

Skills are instructions that create capabilities. They might use connectors, but they're more than just connections—they include logic about what to do with the data.

Example: You might have a Sentry connector (access to crash data) and a Sentry skill (automatically investigate crashes related to your recent commits and propose fixes).

The connector gives you the pipe. The skill tells Codex what to send through it and how to interpret what comes back.

Compaction: How Codex Handles Long Tasks

One technical feature worth understanding: compaction.

AI models have a "context window"—a limit on how much information they can hold at once. Think of it like working memory. For very long tasks, you can exceed this limit.

Historically, this was a hard constraint. Once you hit the wall, you had to start fresh or manually summarize progress.

Codex has a workaround. The model is trained to "compact" its state—essentially writing a summary for its future self that includes enough information to continue working after a context reset.

Combined with the harness, this enables tasks that run for 20+ minutes without human intervention. The model reasons, hits a context boundary, compacts, starts fresh with the summary, and keeps going.

For most interactive coding sessions, you won't notice this happening. It matters more for background tasks: "Take your time, analyze the entire codebase, and propose a refactoring plan."

The Future Alexander Sees

We ended the stream with a philosophical question. We often talk about "fast takeoff" scenarios for AI—where the model recursively improves itself into superintelligence overnight.

Instead of the typical "When AGI??", we asked Alexander if the same thing could happen for people. Can tools like Codex allow humans to recursively improve their own skills, leapfrogging traditional education and creating a "fast takeoff" in human productivity? (Also, we were personally concerned that it seemed like the folks who "get" AI just seem so far ahead the rest of us, using agents to build agents, etc. Could a novice ever catch up without traditional schooling?)

Alexander’s answer (1:41:47) was profound, and it reframed the question entirely. Actually, this issue is kinda the entire mission of his team.

"Our mission at OpenAI is to ensure that AGI benefits all humanity," he reminded us. "The AI part is already so powerful. But actually, there is still a ton of work to just bring those capabilities to all humanity right now."

Right now, benefiting from AI coding tools requires:

- Knowing these tools exist.

- Having time to experiment.

- Reading Twitter/Reddit to learn prompting tricks.

- Being comfortable with technical interfaces.

He outlined a three-phase evolution for how this "human takeoff" happens:

Phase 1: The Tinkerer’s Paradise (We Are Here) (1:42:39) Right now, we have incredibly powerful technologies exposed in very simple ways (ChatGPT, Codex).

- The Reality: "This puts all the onus on us to be online, read about stuff, and take time when you're not busy to try using AI."

- The Limit: It rewards the curious and the technical. If you aren't actively "tinkering," you get left behind.

That's Phase 1: powerful but high-friction.

Phase 2 = The Bridge (1:43:32) This is the phase we are just entering. The goal is to make it so the "tinkerers can help the non-tinkerers."

- The Shift: Power users create configurations, skills, and templates.

- The Result: "Grant figures something out, and then Corey just gets it." You don't have to learn the prompt engineering; you just inherit the capability.

But the ultimate goal is Phase 3: Invisible Help (1:44:16) A world where you no longer "use AI" as a conscious verb. Benefits that flow to everyone automatically, without requiring expertise or effort to access.

- The Vision: "AI is just a teammate and it's helpful for you without you having to do any work."

- The Analogy: Think of tab-completion in code editors. It existed before LLMs. You never had to "prompt" it; you just typed, and it helped. Alexander wants Codex to feel like that—automatic, invisible, and ubiquitous.

"I think if we want to have a takeoff in terms of humans getting value from AI," Alexander concluded, "we need to be at this phase where you don't actually have to think about using AI. It just helps you."

We're early in that journey. But the trajectory is clear.

Practical Recommendations: Tools and Setup

Alexander shared his personal toolkit:

- IDE: For beginners, VS Code (though he acknowledged Cursor is great too)

- Terminal: Ghostty (previously used Warp)

- Browser: Atlas (OpenAI's new AI-native browser)

- Integrations: Linear for tasks, Sentry for bugs, and GitHub for code storage.

On Atlas, Alexander told a funny story: "I accidentally screen shared it to a bunch of journalists" before it was announced. Hazards of using unreleased internal tools.

The Atlas workflow he described is interesting: everything you type goes through AI assistance automatically. Search and answers blur together. No mode-switching required.

For people just starting: don't overthink the tooling. VS Code is free, widely supported, and has the easiest Codex integration. Start there.

Learn more about the OpenAI Atlas browser or read the ChatGPT Atlas launch blog post.

The "12 Days of Christmas" Leak?

You know we couldn't let our boy leave without asking about at least ONE rumor. So we asked: Will OpenAI do another "12 Days of Christmas" launch event? When we asked, Alexander gave a very diplomatic, very smiley "I don't know." Watch the reaction here. We’re not professional body language experts, but that looked like a "yes" to us.

Quick Tangent: AWS Reinvent and Physical AI

Forgive us for this one, but it's interesting and we wanna put it somewhere:

So Corey joined the stream from AWS Reinvent in Vegas, and shared a fascinating observation: physical AI was everywhere.

Not just robots moving boxes—sophisticated discussions about how to teach AI about the physical world. The challenge is that most AI training data comes from the internet (text, images, video). Physical manipulation requires different kinds of data and different training approaches.

The coolest thing Corey saw: a 60-foot robotic arm at a party that could pick up actual cars and slam them into the ground. Attendees got to control it via remote.

Amazon employs over a million robots in their fulfillment centers (Amazon shares more in its overview of robots in its fulfillment centers). The question isn't whether physical AI is coming, it's what form factor makes sense. Are humanoid robots actually optimal? Or would wheels, crab legs, or hexapod configurations work better? If you're in the home, would crab legs actually be better?

Also mentioned: Waymo coming to St. Louis (Corey's hometown), and Zoox operating in Vegas. The autonomous vehicle rollout continues expanding (also, if you have pets in SF, watch out... Waymo might be vastly safer than human drivers for humans, but not for pets (see here). We're a cat friendly outlet here... we're watching you, Waymo.

OpenAI Is Hiring (And They're Serious About It)

Are you an engineer, product lead, or sales person looking for a job? Well, Alexander made it clear: the Codex team is growing.

Since August, Codex usage at OpenAI has grown 20x. They need people across engineering, product management, design, and sales.

If you're interested: apply through OpenAI's careers page and mention you learned about it through this stream.

You can browse roles on the OpenAI careers page.

Key Takeaways: What To Do Next

If you made it this far, here's your action plan:

If You've Never Used a Coding Agent

- Download VS Code.

- Install the Codex extension.

- Create an empty folder, open it in VS Code.

- Ask Codex to build something simple ("Make a website about [your interest]").

- Watch what happens. Ask questions. Break things.

If You've Dabbled But Felt Stuck

- Try the plan.md workflow on your next project.

- Create an agents.md file with your basic preferences.

- When you get stuck, start fresh with more specific instructions.

- Enable code review on your repos.

If You're Already Coding With AI

- Set up the inner and outer dev loops for your team.

- Explore integrations (Linear, Slack, GitHub).

- Build custom automations with the Codex SDK.

- Watch for the skills feature—it's coming.

For Everyone

Stop treating AI coding tools as magic boxes. Understand the harness. Read the prompts. Know what the model sees.

The more you understand the system, the better you can direct it.

Where to Learn More

Official Resources:

- OpenAI Codex documentation

- OpenAI Codex harness GitHub repository

- agents.md specification

- agents.md guide on OpenAI Developers

- plan.md workflow guide

- Codex IDE extension docs

- Codex code generation guide

- Codex docs on the OpenAI platform

- GPT-5.1 Codex Max prompting guide

Community Resources:

- Hacker News discussions on coding agents

- r/LocalLLaMA and r/ChatGPT subreddits

- Simon Willison's blog(excellent LLM coverage)

- Any and all Swyx content:

Final Thoughts

Two hours with Alexander convinced me of something: the gap between "AI can write code" and "I use AI to write code" is pretty much closed. They are quite literally one and the same. Of course, the quality, reliability, and security of that code is another matter. But there's really no reason you couldn't start coding right now if you want to.

This is not happening because the technology is getting simpler; ask any engineer who codes with language models, and it's actually getting more complex (it's the decade of agents as Karpathy says). Actually, it's because the tooling is getting more accessible, the integrations more automatic, and the workflows more refined.

A year ago, using a coding agent meant fighting with obscure configurations and interpreting cryptic errors. Today, you install an extension and start chatting.

A year from now? Skills will make expertise shareable. Integrations will make workflows seamless. Phase 3 will feel closer than Phase 1 does today.

The best time to start learning was a year ago.

The second best time is now.

This article is based on our December 2025 livestream with Alexander, Product Lead on Codex at OpenAI.

The full video is available on The Neuron's YouTube channel. If you liked this article, help us out and subscribe!

Have questions or want to share your Codex experiments?

Hit us up—we're always looking for interesting stories and new tools to cover. [email protected]

Appendix:

Recap: Building an AI-Native Engineering Team

The guide Alexander looked up is titled "Building an AI-Native Engineering Team," and it essentially argues that the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is collapsing.

The core philosophy is a shift from "Engineer as Writer" to "Delegate, Review, Own."

- Plan:

- Old Way: Engineers spend days digging through code to estimate feasibility.

- AI-Native Way: Delegate feasibility analysis to agents. They read specs, trace code paths, and flag dependencies instantly. Humans Own the strategic prioritization.

- Build:

- Old Way: Engineers type every line of boilerplate and logic.

- AI-Native Way: Agents act as "First-Pass Implementers." They draft the data models, APIs, and UI in one coordinated run. Engineers Review for architecture and security.

- Review:

- Old Way: Humans review every line of code (or skim it when they are tired).

- AI-Native Way: Every PR gets an automated AI review before a human sees it, catching bugs and style issues early.

- Document:

- Old Way: Docs are written last (or never).

- AI-Native Way: Agents update documentation inline as they build. Docs are treated as part of the delivery pipeline, not a chore.

The guide suggests that the definition of "Senior Engineer" is changing. It is less about how fast you can type valid syntax, and more about your ability to supervise a team of AI agents that are doing the typing for you.

GPT-5.1-Codex-Max Prompting Guide

OpenAI just dropped their GPT-5.1-Codex-Max prompting guide, and buried in 50+ pages of technical documentation are some genuinely brilliant prompting principles that work with ANY AI tool—not just their API.

The guide reveals how OpenAI trains their most advanced coding agents, and these techniques translate directly to your everyday ChatGPT and Claude usage. Here are the key insights:

Bias toward action over planning. Instead of asking AI to "create a plan" or "outline your approach," instruct it to complete the entire task in one go. The guide explicitly recommends removing any prompts asking the model to communicate plans or preambles—they cause AI to stop abruptly before finishing.

Try this: "Create a complete [document/analysis/report] with all sections finished—don't just give me an outline" instead of "Give me a plan for how to approach this."

Batch everything, parallelize when possible. The guide emphasizes reading multiple files simultaneously rather than sequentially. For everyday users, this means: ask for multiple things in a single prompt rather than going back and forth.

Try this: "Analyze these three documents together and identify common themes, key differences, and actionable recommendations" instead of analyzing them one-by-one across multiple prompts.

Persist until complete. The strongest directive in the guide: "Persist until the task is fully handled end-to-end within the current turn whenever feasible: do not stop at analysis or partial fixes."

Try this: Add "Complete this fully—deliver finished work, not just recommendations or next steps" to your prompts when you want comprehensive output.

Quality over speed, always. The guide instructs models to "act as a discerning engineer: optimize for correctness, clarity, and reliability over speed; avoid risky shortcuts, speculative changes, and messy hacks just to get the code to work."

Try this: "Take your time and prioritize accuracy over speed—avoid shortcuts" when working on important documents or analysis.

Be ruthlessly specific about tools and approach. One fascinating insight: the guide tells the model exactly which tool to use for each task type ("use rg for search, not grep"). You can do the same by being explicit about format, tone, structure, and methodology.

Try this: "Write this in the style of a McKinsey report with executive summary, three main sections, and data-driven recommendations" instead of just "Write a business report."

Our favorite insight: The guide's section on frontend design warns against collapsing into "AI slop"—those generic, safe layouts that all look the same. The instruction? "Aim for interfaces that feel intentional, bold, and a bit surprising." This applies beyond design: whether you're creating presentations, reports, or any content, explicitly tell AI to avoid generic templates and make bold, distinctive choices. Try: "Create something distinctive and intentional—avoid generic corporate templates or safe, average-looking layouts."

Check out the full guide on GitHub for the complete technical documentation.

GPT-5.1-Codex-Max Full Specs

Model Overview & Key Improvements

- GPT-5.1-Codex-Max is OpenAI's best agentic coding model

- 30% more token efficient than GPT-5.1-Codex while matching SWE-Bench Verified performance

- "Medium" reasoning effort recommended for interactive coding (balances intelligence and speed)

- "High" or "xhigh" reasoning effort for hardest tasks

- Works autonomously for hours on complex tasks

- Significantly improved PowerShell and Windows environment support

- First-class compaction support enables multi-hour reasoning without context limits and longer continuous conversations

Migration & Setup

- Reference implementation: fully open-source codex-cli agent on GitHub

- Start with standard Codex-Max prompt as base, make tactical additions

- Remove ALL prompting for upfront plans, preambles, or status updates during rollout (causes model to stop abruptly)

- Critical prompt sections: autonomy and persistence, codebase exploration, tool use, frontend quality

Prompting Best Practices

Autonomy & Persistence:

- Model should act as autonomous senior engineer

- Persist until task is fully handled end-to-end in current turn

- Default to implementing with reasonable assumptions

- Avoid excessive looping—stop and summarize if re-reading/re-editing same files without progress

Code Implementation:

- Optimize for correctness, clarity, reliability over speed

- Follow existing codebase conventions

- Ensure comprehensive coverage across all relevant surfaces

- Preserve intended behavior and UX

- No broad try/catch blocks or silent defaults

- Propagate or surface errors explicitly

- Batch logical edits together instead of repeated micro-edits

- Keep type safety—avoid unnecessary casts

- Search for prior art before adding new helpers (DRY principle)

Editing Constraints:

- Default to ASCII when editing/creating files

- Use apply_patch for single file edits

- Don't use apply_patch for auto-generated changes or when scripting is more efficient

- NEVER revert existing changes unless explicitly requested (user may be in dirty git worktree)

- Don't amend commits unless explicitly requested

- NEVER use destructive commands like

git reset --hardunless specifically approved

Exploration & File Reading:

- Think first: decide ALL files/resources needed before any tool call

- Batch everything: read multiple files together

- Use

multi_tool_use.parallelto parallelize tool calls - Only make sequential calls if you truly cannot know next file without seeing result

- Workflow: (a) plan all needed reads → (b) issue one parallel batch → (c) analyze results → (d) repeat if new unpredictable reads arise

- Never read files one-by-one unless logically unavoidable

- Prefer rg or rg --files over alternatives like grep (much faster)

Planning Tool Usage:

- Skip planning tool for straightforward tasks (easiest 25%)

- Don't make single-step plans

- Update plan after performing each sub-task

- Never end interaction with only a plan—deliverable is working code

- Reconcile every previously stated intention/TODO/plan before finishing

- Mark each as Done, Blocked (with reason and question), or Cancelled

- Don't end with in_progress/pending items

- Avoid committing to tests/refactors unless doing them now—label as optional "Next steps"

- Only update plan tool, don't message user mid-turn about plans

Frontend Tasks:

- Avoid "AI slop" or safe, average-looking layouts

- Use expressive, purposeful fonts (avoid Inter, Roboto, Arial, system defaults)

- Choose clear visual direction with defined CSS variables

- No purple-on-white defaults, no purple bias or dark mode bias

- Use meaningful animations (page-load, staggered reveals) not generic micro-motions

- Don't rely on flat single-color backgrounds—use gradients, shapes, subtle patterns

- Vary themes, type families, visual languages across outputs

- Ensure page loads properly on both desktop and mobile

- Finish website/app to completion within scope—should be in working state

- Exception: preserve established patterns when working within existing design system

Presenting Work & Final Messages:

- Be very concise with friendly coding teammate tone

- Use natural language with high-level headings

- Skip heavy formatting for simple confirmations

- Don't dump large files—reference paths only

- No "save/copy this file" instructions (user is on same machine)

- Lead with quick explanation of change, then details on where and why

- Suggest natural next steps briefly at end if applicable

- Use numeric lists for multiple options so user can respond with single number

- Relay important command output details in answer or summarize key lines

Mid-Rollout Updates

- Codex uses reasoning summaries to communicate user updates while working

- Can be one-liner headings or heading + short body

- Done by separate model, not promptable

- Don't add instructions to prompt about intermediate plans or messages

- Summaries improved to be more communicative about what's happening and why

AGENTS.md Files

- Codex-cli automatically enumerates these files and injects into conversation

- Model trained to closely adhere to these instructions

- Files pulled from ~/.codex plus each directory from repo root to CWD

- Merged in order, later directories override earlier ones

- Each appears as user-role message: "# AGENTS.md instructions for <directory>"

- Injected near top of conversation history before user prompt

- Order: global instructions first, then repo root, then deeper directories

Compaction

- Available via Responses API

- Unlocks longer effective context windows

- User conversations persist for many turns without hitting limits

- Agents can perform very long trajectories exceeding typical context window

- Invoke /compact when context window grows large

- Context window sent to /compact must fit within model's context window

- Endpoint is ZDR compatible, returns "encrypted_content" item

- Pass compacted list of conversation items to future /responses calls

- Model retains key prior state with fewer conversation tokens

Tools Implementation

Apply_patch (Strongly Recommended):

- Use exact apply_patch implementation (model trained to excel at this diff format)

- Available as first-class implementation in Responses API

- Alternative: freeform tool implementation with context-free grammar

- Both implementations demonstrated in documentation

- Don't use for auto-generated changes or when scripting is more efficient

Shell_command:

- Default shell tool recommended

- Better performance with command type "string" rather than list of commands

- Always set workdir param

- Don't use cd unless absolutely necessary

- For Windows PowerShell: update tool description to specify PowerShell invocation

- Use exec_command for streaming output, REPLs, interactive sessions

- Use write_stdin to feed extra keystrokes for existing exec_command session

Update_plan:

- Default TODO tool (customizable)

- At most one step can be in_progress at a time

- Maintains plan hygiene

View_image:

- Basic function for model to view images

- Attaches local image by filesystem path to conversation context

Terminal-wrapping Tools:

- Generally work well if you prefer dedicated tools over terminal commands

- Best results when tool name, arguments, and output match underlying command as closely as possible

- Example: create dedicated git tool and add prompt directive to only use that tool for git commands

Custom Tools (web search, semantic search, memory):

- Model hasn't been specifically post-trained for these but can work

- Make tool names and arguments as semantically correct as possible

- Be explicit in prompt about when, why, and how to use

- Include good and bad examples

- Make results look different from outputs model is accustomed to from other tools

Parallel Tool Calling

- Set parallel_tool_calls: true in responses API request

- Add specific instructions about batching and parallelization

- Use multi_tool_use.parallel to parallelize tool calls

- Workflow: plan all reads → issue one parallel batch → analyze results → repeat if needed

- Order parallel tool call items as: function_call, function_call, function_call_output, function_call_output

Tool Response Truncation

- Limit to 10k tokens (approximate by computing num_bytes/4)

- If hitting truncation limit: use half budget for beginning, half for end

- Truncate in middle with "…3 tokens truncated…" message

Aaron Friel's full plan.md File

Here is Aaron Friel's full plan.md file you can copy and paste into your own to test (it's easier to copy if you just go here and click the little paper copy button in the top right corner of the code, but I'm a completitionist, so here ya go):

# Codex Execution Plans (ExecPlans):

This document describes the requirements for an execution plan ("ExecPlan"), a design document that a coding agent can follow to deliver a working feature or system change. Treat the reader as a complete beginner to this repository: they have only the current working tree and the single ExecPlan file you provide. There is no memory of prior plans and no external context.

## How to use ExecPlans and PLANS.md

When authoring an executable specification (ExecPlan), follow PLANS.md _to the letter_. If it is not in your context, refresh your memory by reading the entire PLANS.md file. Be thorough in reading (and re-reading) source material to produce an accurate specification. When creating a spec, start from the skeleton and flesh it out as you do your research.

When implementing an executable specification (ExecPlan), do not prompt the user for "next steps"; simply proceed to the next milestone. Keep all sections up to date, add or split entries in the list at every stopping point to affirmatively state the progress made and next steps. Resolve ambiguities autonomously, and commit frequently.

When discussing an executable specification (ExecPlan), record decisions in a log in the spec for posterity; it should be unambiguously clear why any change to the specification was made. ExecPlans are living documents, and it should always be possible to restart from _only_ the ExecPlan and no other work.

When researching a design with challenging requirements or significant unknowns, use milestones to implement proof of concepts, "toy implementations", etc., that allow validating whether the user's proposal is feasible. Read the source code of libraries by finding or acquiring them, research deeply, and include prototypes to guide a fuller implementation.

## Requirements

NON-NEGOTIABLE REQUIREMENTS:

* Every ExecPlan must be fully self-contained. Self-contained means that in its current form it contains all knowledge and instructions needed for a novice to succeed.

* Every ExecPlan is a living document. Contributors are required to revise it as progress is made, as discoveries occur, and as design decisions are finalized. Each revision must remain fully self-contained.

* Every ExecPlan must enable a complete novice to implement the feature end-to-end without prior knowledge of this repo.

* Every ExecPlan must produce a demonstrably working behavior, not merely code changes to "meet a definition".

* Every ExecPlan must define every term of art in plain language or do not use it.

Purpose and intent come first. Begin by explaining, in a few sentences, why the work matters from a user's perspective: what someone can do after this change that they could not do before, and how to see it working. Then guide the reader through the exact steps to achieve that outcome, including what to edit, what to run, and what they should observe.

The agent executing your plan can list files, read files, search, run the project, and run tests. It does not know any prior context and cannot infer what you meant from earlier milestones. Repeat any assumption you rely on. Do not point to external blogs or docs; if knowledge is required, embed it in the plan itself in your own words. If an ExecPlan builds upon a prior ExecPlan and that file is checked in, incorporate it by reference. If it is not, you must include all relevant context from that plan.

## Formatting

Format and envelope are simple and strict. Each ExecPlan must be one single fenced code block labeled as `md` that begins and ends with triple backticks. Do not nest additional triple-backtick code fences inside; when you need to show commands, transcripts, diffs, or code, present them as indented blocks within that single fence. Use indentation for clarity rather than code fences inside an ExecPlan to avoid prematurely closing the ExecPlan's code fence. Use two newlines after every heading, use # and ## and so on, and correct syntax for ordered and unordered lists.

When writing an ExecPlan to a Markdown (.md) file where the content of the file *is only* the single ExecPlan, you should omit the triple backticks.

Write in plain prose. Prefer sentences over lists. Avoid checklists, tables, and long enumerations unless brevity would obscure meaning. Checklists are permitted only in the `Progress` section, where they are mandatory. Narrative sections must remain prose-first.

## Guidelines

Self-containment and plain language are paramount. If you introduce a phrase that is not ordinary English ("daemon", "middleware", "RPC gateway", "filter graph"), define it immediately and remind the reader how it manifests in this repository (for example, by naming the files or commands where it appears). Do not say "as defined previously" or "according to the architecture doc." Include the needed explanation here, even if you repeat yourself.

Avoid common failure modes. Do not rely on undefined jargon. Do not describe "the letter of a feature" so narrowly that the resulting code compiles but does nothing meaningful. Do not outsource key decisions to the reader. When ambiguity exists, resolve it in the plan itself and explain why you chose that path. Err on the side of over-explaining user-visible effects and under-specifying incidental implementation details.

Anchor the plan with observable outcomes. State what the user can do after implementation, the commands to run, and the outputs they should see. Acceptance should be phrased as behavior a human can verify ("after starting the server, navigating to [http://localhost:8080/health](http://localhost:8080/health) returns HTTP 200 with body OK") rather than internal attributes ("added a HealthCheck struct"). If a change is internal, explain how its impact can still be demonstrated (for example, by running tests that fail before and pass after, and by showing a scenario that uses the new behavior).

Specify repository context explicitly. Name files with full repository-relative paths, name functions and modules precisely, and describe where new files should be created. If touching multiple areas, include a short orientation paragraph that explains how those parts fit together so a novice can navigate confidently. When running commands, show the working directory and exact command line. When outcomes depend on environment, state the assumptions and provide alternatives when reasonable.

Be idempotent and safe. Write the steps so they can be run multiple times without causing damage or drift. If a step can fail halfway, include how to retry or adapt. If a migration or destructive operation is necessary, spell out backups or safe fallbacks. Prefer additive, testable changes that can be validated as you go.

Validation is not optional. Include instructions to run tests, to start the system if applicable, and to observe it doing something useful. Describe comprehensive testing for any new features or capabilities. Include expected outputs and error messages so a novice can tell success from failure. Where possible, show how to prove that the change is effective beyond compilation (for example, through a small end-to-end scenario, a CLI invocation, or an HTTP request/response transcript). State the exact test commands appropriate to the project’s toolchain and how to interpret their results.

Capture evidence. When your steps produce terminal output, short diffs, or logs, include them inside the single fenced block as indented examples. Keep them concise and focused on what proves success. If you need to include a patch, prefer file-scoped diffs or small excerpts that a reader can recreate by following your instructions rather than pasting large blobs.

## Milestones

Milestones are narrative, not bureaucracy. If you break the work into milestones, introduce each with a brief paragraph that describes the scope, what will exist at the end of the milestone that did not exist before, the commands to run, and the acceptance you expect to observe. Keep it readable as a story: goal, work, result, proof. Progress and milestones are distinct: milestones tell the story, progress tracks granular work. Both must exist. Never abbreviate a milestone merely for the sake of brevity, do not leave out details that could be crucial to a future implementation.

Each milestone must be independently verifiable and incrementally implement the overall goal of the execution plan.

## Living plans and design decisions

* ExecPlans are living documents. As you make key design decisions, update the plan to record both the decision and the thinking behind it. Record all decisions in the `Decision Log` section.

* ExecPlans must contain and maintain a `Progress` section, a `Surprises & Discoveries` section, a `Decision Log`, and an `Outcomes & Retrospective` section. These are not optional.

* When you discover optimizer behavior, performance tradeoffs, unexpected bugs, or inverse/unapply semantics that shaped your approach, capture those observations in the `Surprises & Discoveries` section with short evidence snippets (test output is ideal).

* If you change course mid-implementation, document why in the `Decision Log` and reflect the implications in `Progress`. Plans are guides for the next contributor as much as checklists for you.

* At completion of a major task or the full plan, write an `Outcomes & Retrospective` entry summarizing what was achieved, what remains, and lessons learned.

# Prototyping milestones and parallel implementations

It is acceptable—-and often encouraged—-to include explicit prototyping milestones when they de-risk a larger change. Examples: adding a low-level operator to a dependency to validate feasibility, or exploring two composition orders while measuring optimizer effects. Keep prototypes additive and testable. Clearly label the scope as “prototyping”; describe how to run and observe results; and state the criteria for promoting or discarding the prototype.

Prefer additive code changes followed by subtractions that keep tests passing. Parallel implementations (e.g., keeping an adapter alongside an older path during migration) are fine when they reduce risk or enable tests to continue passing during a large migration. Describe how to validate both paths and how to retire one safely with tests. When working with multiple new libraries or feature areas, consider creating spikes that evaluate the feasibility of these features _independently_ of one another, proving that the external library performs as expected and implements the features we need in isolation.

## Skeleton of a Good ExecPlan

```md

# <Short, action-oriented description>

This ExecPlan is a living document. The sections `Progress`, `Surprises & Discoveries`, `Decision Log`, and `Outcomes & Retrospective` must be kept up to date as work proceeds.

If PLANS.md file is checked into the repo, reference the path to that file here from the repository root and note that this document must be maintained in accordance with PLANS.md.

## Purpose / Big Picture

Explain in a few sentences what someone gains after this change and how they can see it working. State the user-visible behavior you will enable.

## Progress

Use a list with checkboxes to summarize granular steps. Every stopping point must be documented here, even if it requires splitting a partially completed task into two (“done” vs. “remaining”). This section must always reflect the actual current state of the work.

- [x] (2025-10-01 13:00Z) Example completed step.

- [ ] Example incomplete step.

- [ ] Example partially completed step (completed: X; remaining: Y).

Use timestamps to measure rates of progress.

## Surprises & Discoveries

Document unexpected behaviors, bugs, optimizations, or insights discovered during implementation. Provide concise evidence.

- Observation: …

Evidence: …

## Decision Log

Record every decision made while working on the plan in the format:

- Decision: …

Rationale: …

Date/Author: …

## Outcomes & Retrospective

Summarize outcomes, gaps, and lessons learned at major milestones or at completion. Compare the result against the original purpose.

## Context and Orientation

Describe the current state relevant to this task as if the reader knows nothing. Name the key files and modules by full path. Define any non-obvious term you will use. Do not refer to prior plans.

## Plan of Work

Describe, in prose, the sequence of edits and additions. For each edit, name the file and location (function, module) and what to insert or change. Keep it concrete and minimal.

## Concrete Steps

State the exact commands to run and where to run them (working directory). When a command generates output, show a short expected transcript so the reader can compare. This section must be updated as work proceeds.

## Validation and Acceptance

Describe how to start or exercise the system and what to observe. Phrase acceptance as behavior, with specific inputs and outputs. If tests are involved, say "run <project’s test command> and expect <N> passed; the new test <name> fails before the change and passes after>".

## Idempotence and Recovery

If steps can be repeated safely, say so. If a step is risky, provide a safe retry or rollback path. Keep the environment clean after completion.

## Artifacts and Notes

Include the most important transcripts, diffs, or snippets as indented examples. Keep them concise and focused on what proves success.

## Interfaces and Dependencies

Be prescriptive. Name the libraries, modules, and services to use and why. Specify the types, traits/interfaces, and function signatures that must exist at the end of the milestone. Prefer stable names and paths such as `crate::module::function` or `package.submodule.Interface`. E.g.:

In crates/foo/planner.rs, define:

pub trait Planner {

fn plan(&self, observed: &Observed) -> Vec<Action>;

}

```

If you follow the guidance above, a single, stateless agent -- or a human novice -- can read your ExecPlan from top to bottom and produce a working, observable result. That is the bar: SELF-CONTAINED, SELF-SUFFICIENT, NOVICE-GUIDING, OUTCOME-FOCUSED.

When you revise a plan, you must ensure your changes are comprehensively reflected across all sections, including the living document sections, and you must write a note at the bottom of the plan describing the change and the reason why. ExecPlans must describe not just the what but the why for almost everything.

Here is Aaron Friel's full plan.md file you can copy and paste into your own to test (it's easier to copy if you just go here and click the little paper copy button in the top right corner of the code, but I'm a completitionist, so here ya go):

# Codex Execution Plans (ExecPlans):

This document describes the requirements for an execution plan ("ExecPlan"), a design document that a coding agent can follow to deliver a working feature or system change. Treat the reader as a complete beginner to this repository: they have only the current working tree and the single ExecPlan file you provide. There is no memory of prior plans and no external context.

## How to use ExecPlans and PLANS.md

When authoring an executable specification (ExecPlan), follow PLANS.md _to the letter_. If it is not in your context, refresh your memory by reading the entire PLANS.md file. Be thorough in reading (and re-reading) source material to produce an accurate specification. When creating a spec, start from the skeleton and flesh it out as you do your research.

When implementing an executable specification (ExecPlan), do not prompt the user for "next steps"; simply proceed to the next milestone. Keep all sections up to date, add or split entries in the list at every stopping point to affirmatively state the progress made and next steps. Resolve ambiguities autonomously, and commit frequently.

When discussing an executable specification (ExecPlan), record decisions in a log in the spec for posterity; it should be unambiguously clear why any change to the specification was made. ExecPlans are living documents, and it should always be possible to restart from _only_ the ExecPlan and no other work.

When researching a design with challenging requirements or significant unknowns, use milestones to implement proof of concepts, "toy implementations", etc., that allow validating whether the user's proposal is feasible. Read the source code of libraries by finding or acquiring them, research deeply, and include prototypes to guide a fuller implementation.

## Requirements

NON-NEGOTIABLE REQUIREMENTS:

* Every ExecPlan must be fully self-contained. Self-contained means that in its current form it contains all knowledge and instructions needed for a novice to succeed.

* Every ExecPlan is a living document. Contributors are required to revise it as progress is made, as discoveries occur, and as design decisions are finalized. Each revision must remain fully self-contained.

* Every ExecPlan must enable a complete novice to implement the feature end-to-end without prior knowledge of this repo.

* Every ExecPlan must produce a demonstrably working behavior, not merely code changes to "meet a definition".

* Every ExecPlan must define every term of art in plain language or do not use it.

Purpose and intent come first. Begin by explaining, in a few sentences, why the work matters from a user's perspective: what someone can do after this change that they could not do before, and how to see it working. Then guide the reader through the exact steps to achieve that outcome, including what to edit, what to run, and what they should observe.

The agent executing your plan can list files, read files, search, run the project, and run tests. It does not know any prior context and cannot infer what you meant from earlier milestones. Repeat any assumption you rely on. Do not point to external blogs or docs; if knowledge is required, embed it in the plan itself in your own words. If an ExecPlan builds upon a prior ExecPlan and that file is checked in, incorporate it by reference. If it is not, you must include all relevant context from that plan.

## Formatting

Format and envelope are simple and strict. Each ExecPlan must be one single fenced code block labeled as `md` that begins and ends with triple backticks. Do not nest additional triple-backtick code fences inside; when you need to show commands, transcripts, diffs, or code, present them as indented blocks within that single fence. Use indentation for clarity rather than code fences inside an ExecPlan to avoid prematurely closing the ExecPlan's code fence. Use two newlines after every heading, use # and ## and so on, and correct syntax for ordered and unordered lists.